Three magic animals keep appearing among the 200+ oil paintings I plan to sell within 2 weeks before putting what remains of my stuff in storage and starting my year-long life experiment in traveling and making art. Hounds, butterflies, and foxes appear in art across many cultures and contexts. Accordingly, their meanings are as varied as humanity—hunter and pray, motif and symbol, friend and accessory.

Hounds

Franz Marc has already painted the best dog paintings in the world, and Mary Oliver has written the most beautiful poems about dogs. Yet in Marc’s vision, there’s a loneliness and angularity about the dog in the snow. While in Oliver’s, the dog is togetherness and comfort.

I love how art can make of one thing at once a notion and its opposite, without deception or contradiction. That way of holding the richness of experience, which can be like that too, seems to be a large part of its power. We all have so much meaning and richness inside us that we have to tell stories all the time to make sense of the world within and without. Giving people tools to tell those stories better—more brightly, more gratefully, more critically—is the service art does to the internal life. That’s what people pay for when they pay for art.

That’s probably why a lot of artists, like Keith Haring, had a policy of not interpreting their art. Giving the viewer all the interpretive power instead. Telling people how to interpret even your own art, in that school of thought, takes a little bit of power away from both the viewer and the art.

Alternately, a lot of story-tellers, like William Blake, have used art to clarify and enrich their own story. There’s no question of whether or not you’re going to offer an interpretation when the whole point of the art in the first place was to illustrate your story.

As a writer first, I fall in the second camp. I’ll tell you what I think my art means. Most of it illustrates my writing in the first place.

Hounds to me symbolize linearity. They’re familiar, comforting, seek tasty animals of fact in straight lines. They’re common. They can be sweet and useful. They’re often presented as the only animal in the world—as in Popperian social science methods texts that teach only linear, falsifiable predictions from linear, falsifiable theories are scientific. For this reason, linear theories and plans can seem like the only animal in forest. But there are plenty of other important meaning-making animals. For one thing, there are also butterflies.

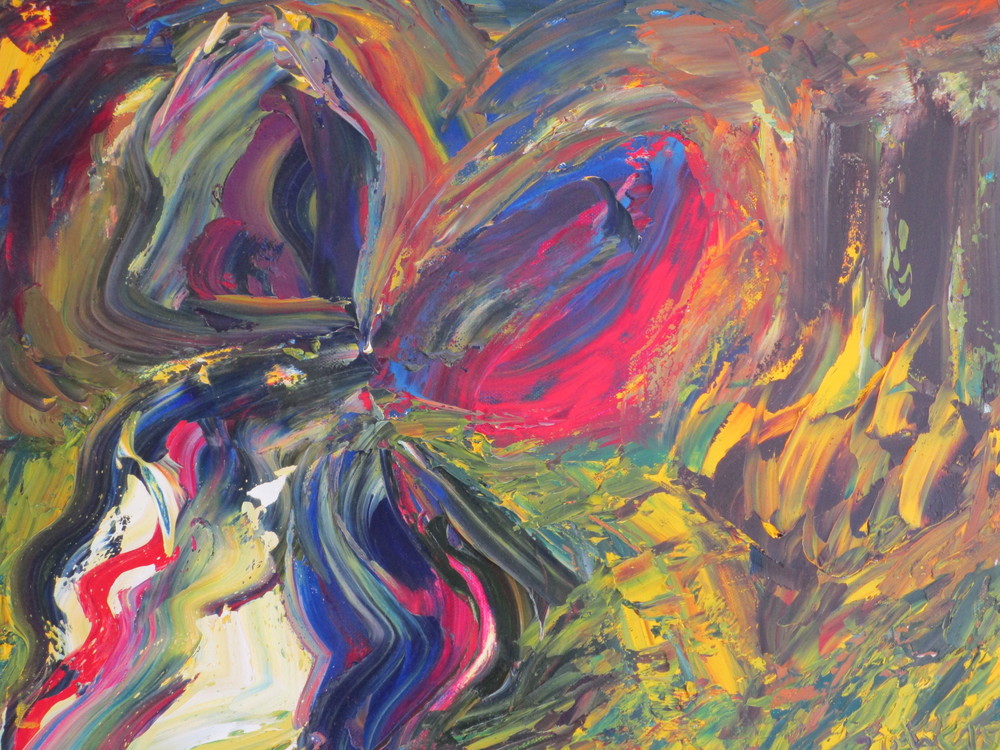

Butterflies

In science, butterflies symbolize chaos. For example, the Lorenz system literally looks like a butterfly. Chaotic theories don’t always generate readily falsifiable hypotheses. That doesn’t make them unscientific.

Thankfully, we can understand a lot about chaotic systems like weather without actually being able to model predictions about it all that well. But weathermen still get the timing and amount of snow wrong all the time. And we still debate to what extent global climate change is man-made, and what it will mean in the future.

A lot of human systems are chaotic, too. Predicting rare events like revolutions and terror attacks is a chaotic systems game.

In more ordinary terms, we often hear some version of the expression: “a butterfly flaps its wings in China, and there’s an earthquake or Timbuktu.” Meaning that sometimes small acts or events have huge, faraway repercussions. That type of effect is inherently non-linear, chaotic. It’s the so-called butterfly effect.

Sometimes, for instance, conflict brings about peace. One might hope anyway that the shadow of the butterfly wing of tragedy can bring attention to old wounds that need healing. I mean tragedy in the classical sense that good actors meet terrible fates despite having their hearts in the right place. And I mean old wounds like the racialized problem of inequality in America.

So in the painting below, the shadow of the butterfly also looks like a man with his hands up, on the ground, alluding to Michael Brown and the problem of lack of recognition between police and communities of color in American today.

Lack of recognition is a prison. We’re not free to develop the goodness in ourselves when we don’t recognize it. We’re not free to help others develop their goodness when we don’t recognize it. And the world isn’t free to flourish when people don’t feel safe enough to risk, economically (in markets) and politically (in democracy).

But risk is scary, and these chaotic systems—markets and democracies—are hard to predict. So a lot of people and communities remain confined in the cloven pine of stasis.

There, internal states remain internal.

There’s no risk of spectacular failure, because there’s no risk—apparently. But the greater risk is arguably from not risking at all.

You might say the opposite of these caged creatures are people who risk great personal cost for the greater good. That those people have butterflies of grace in their faces.

Looking at people like I’m going to draw or paint them always brings out the butterfly. Recognizing the goodness in people tends to bring it out like that.

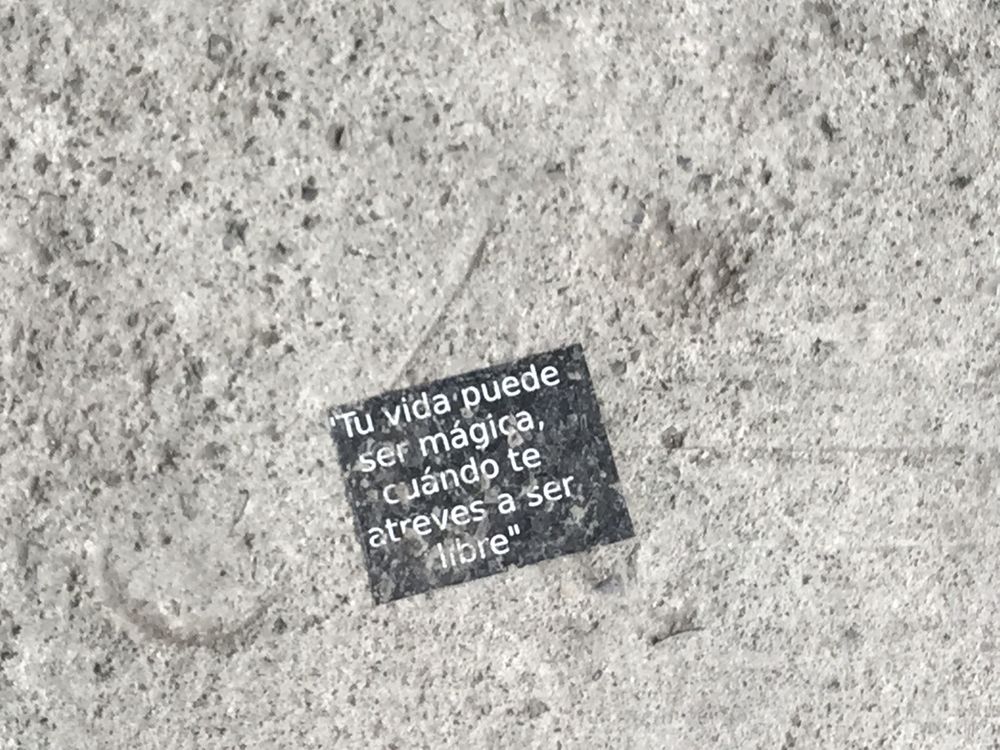

Butterflies also turn out to be a significant motif in Mexican visual culture (arts, crafts, advertising, fabric) —as I learned after photographing and painting them for months and then feeling called to Mexico City last month.

As the sidewalk there said, life can be magic when you remember to be free.

Foxes

In the same way that hounds and butterflies mean lots of things to lots of people, foxes are rich in associative possibility. To some they mean protection or comfort. To others hunger or wiliness, or their combination—the willingness to steal chickens.

To me, the fox symbolizes all those things and more. In theoretical terms, a fox theory is the rare synthesis of linear and chaotic—the meta-theory that often eludes us.

For example, relativity and quantum physics don’t yet square into a unified theory.

This is also a problem in fluid systems modeling. Laminar flow regimes are linear and turbulent flow regimes are chaotic systems, and we don’t yet have a meta-theory fitting them together.

Similarly, we don’t have a unified theory of justice that combines the chaos of internal states and human as opposed to rule-bound interactions with the linearity of procedural justice and justice as fairness. I think the synthesis is something called justice as forgiveness. But I’m more interested in trying to make it with tools like art, faith, and entrepreneurship than writing academic stuff about it.

Hounds, Butterflies, and Foxes

So I tried to envision what it looks like for linear hound and chaotic butterfly theories to fit together in integrated fox theories.

I pictured them on the smiling face of truth I’ve written and painted about before.

And in the tree where the fox might hide from hounds or the butterfly might be confined.

But in the end, what felt most whole and right for envisioning Kit Fox, as I call the character of this linear-chaotic synthesis in the story she lives in in my head, was simply darkness. Falling through the night, as from one universe to another. Or maybe she’s only coming down from the tree.