There is no record of my first attempts to sketch to paint a homunculus for my dear friend Hanka the reproductive biologist, which is doubly lucky. First because they were hideous, misshapen, golem-like creatures. That’s the whole point, homunculi being strange, distorted miniatures. Think of the Mayan origin story of the first attempted humans—made of mud, so flimsy they dissolved in water. Think lumpy, living bits of clay, with hugely over-long arms or legs, lips or noses, like troll dolls or Gumby, but less friendly.

And second because that was the wrong and lesser idea of a homunculus, aesthetically and conceptually. Hanka kindly took my first sketches in stride and pointed me to Hartsoeker’s superior version, a late 17th century microscope inventor’s envisioning of how perhaps a whole human being was holding his knees already inside a single sperm—a poetic, visual version of Monty Python’s “Every Sperm is Sacred.“

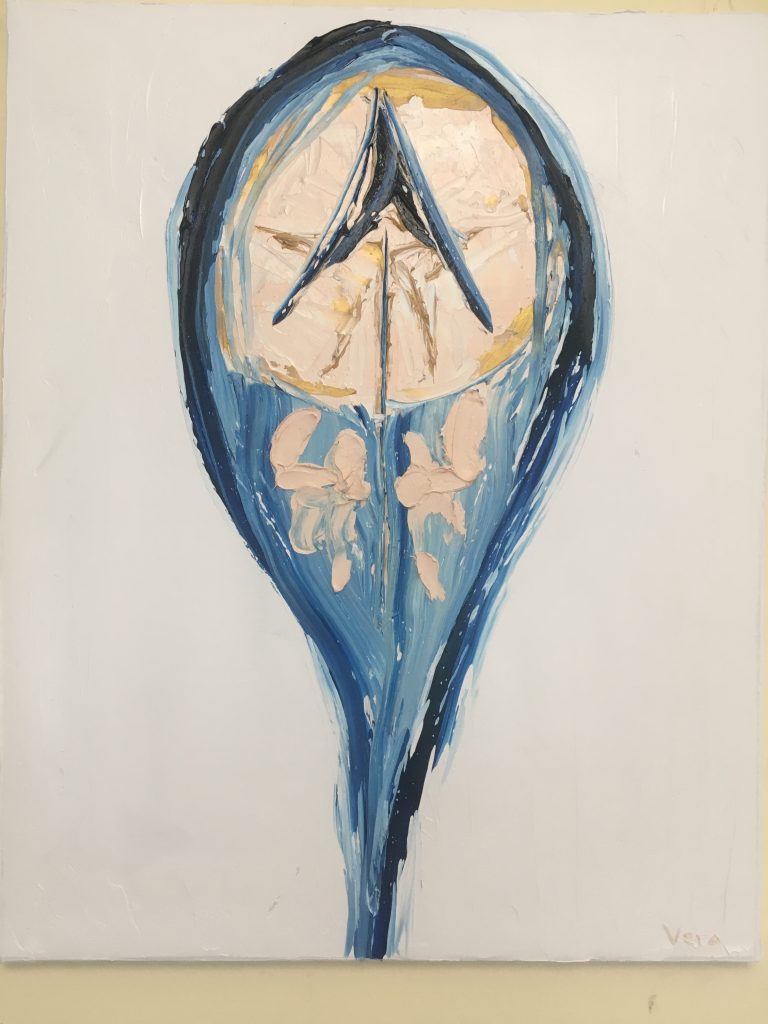

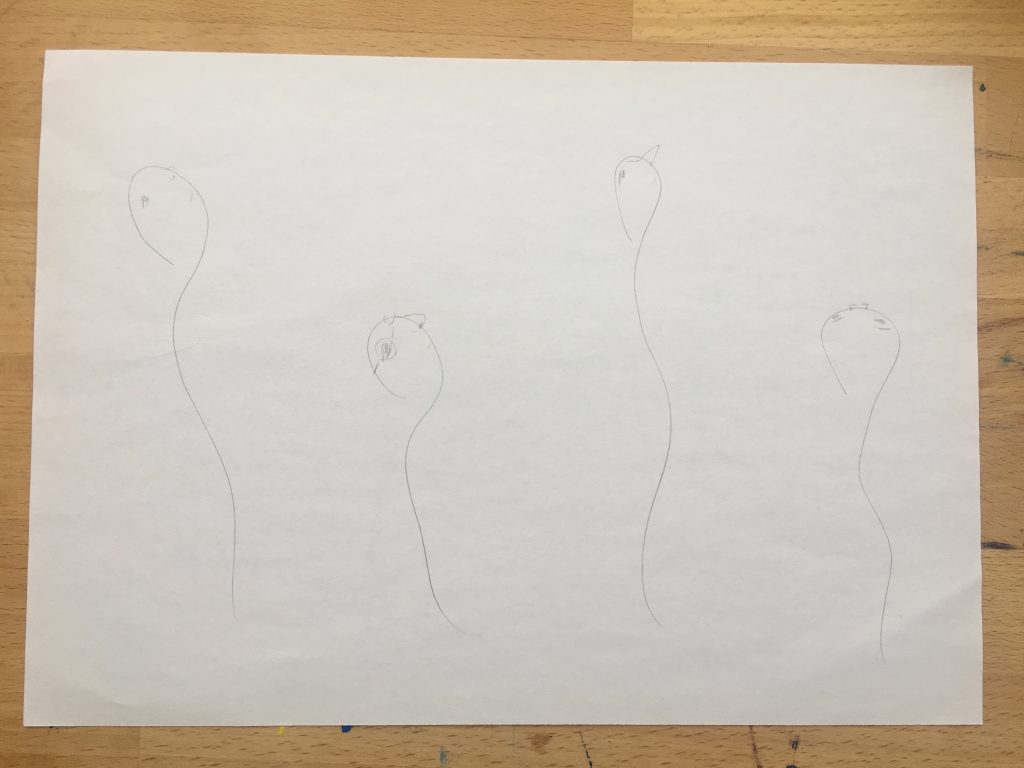

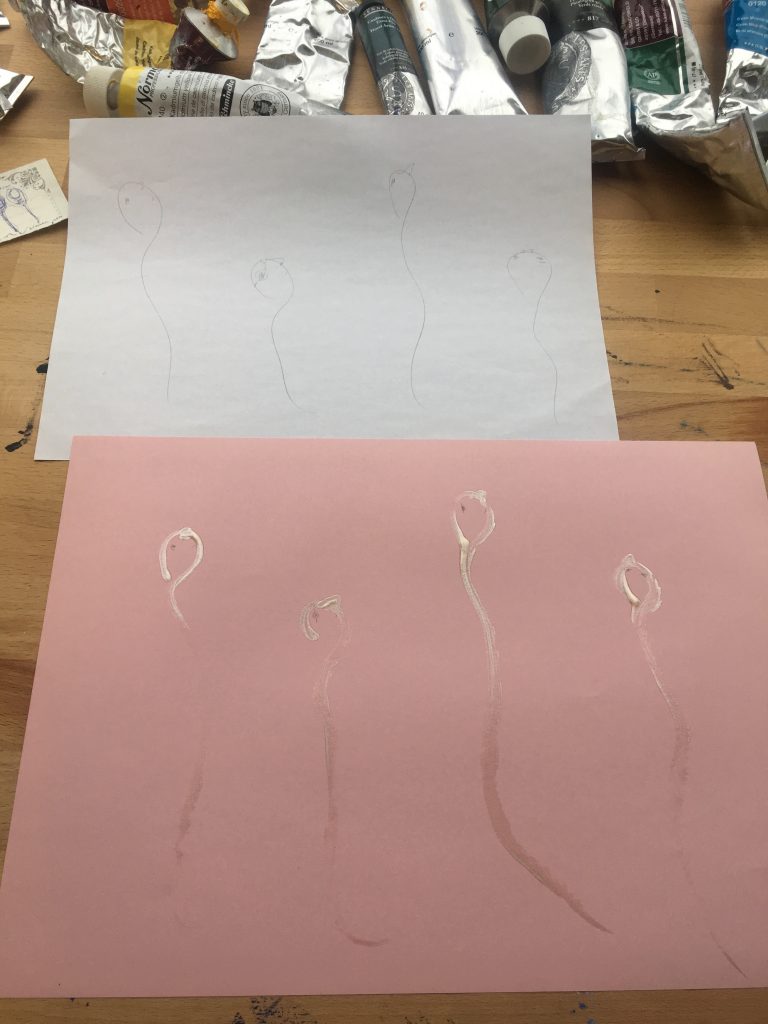

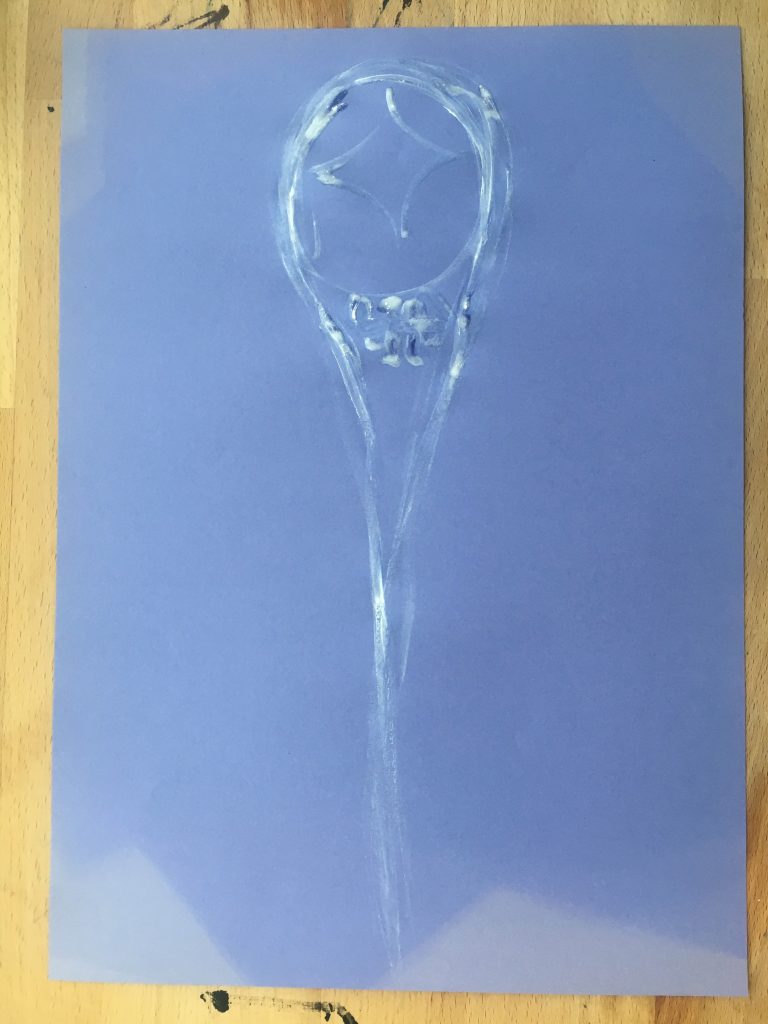

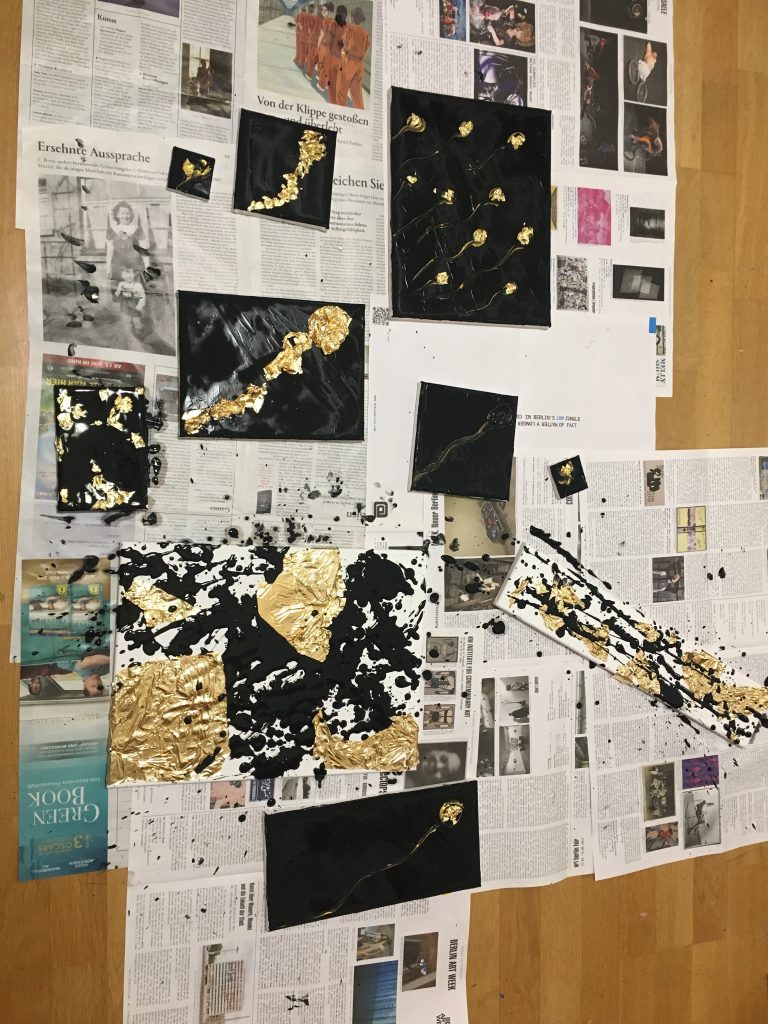

I liked Hartsoecker so much, I tried being faithful to him at first…

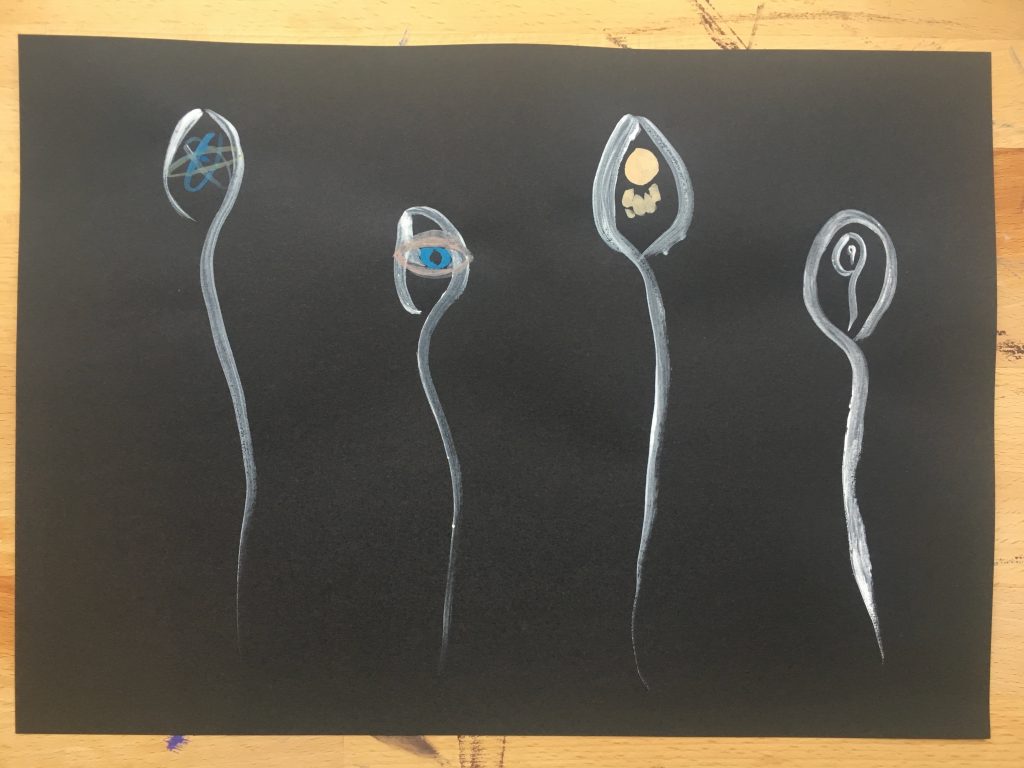

But while I could get the feel right in the strokes, and execute on color, graphically they were all wrong.

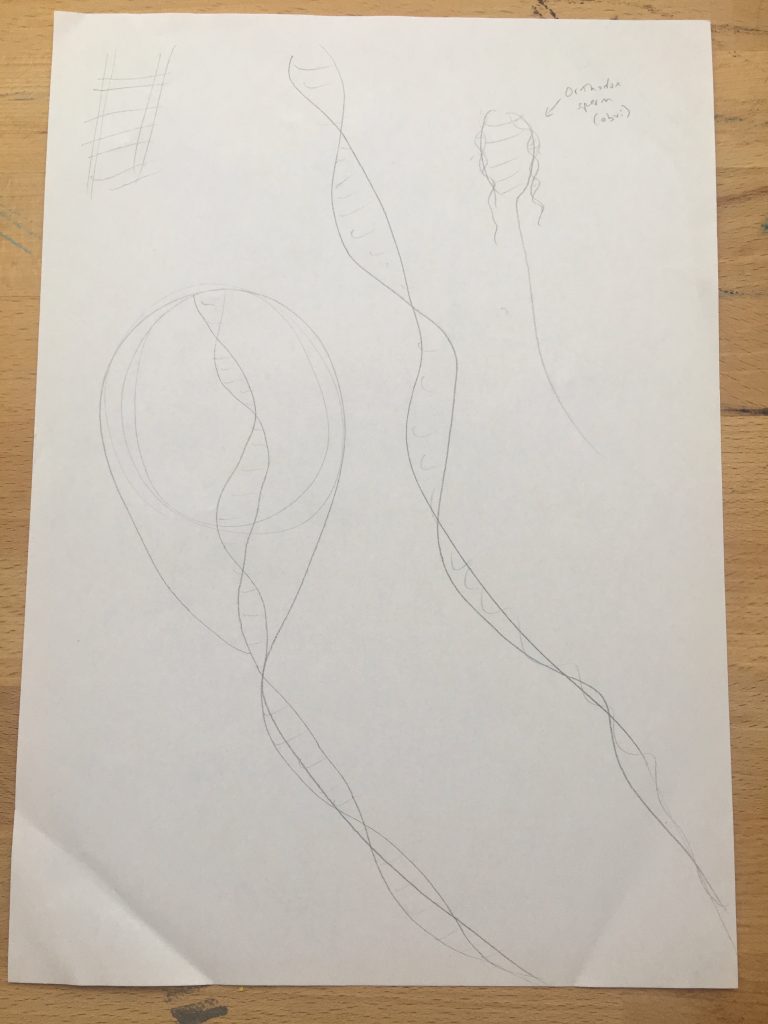

When wrong, one reads. Carol Rumens had a lovely poetry piece in The Guardian recently that mentioned Bentley and Chakravatrula’s research on cell behavior making

“a good case for the hypothesis that cell activity is ‘a perception-action process.’ In other words, that cells engage in a process ‘analogous to a human moving their eyes or their heads or their bodies to create and interact with variables in optic flow.’ Cells make decisions!”

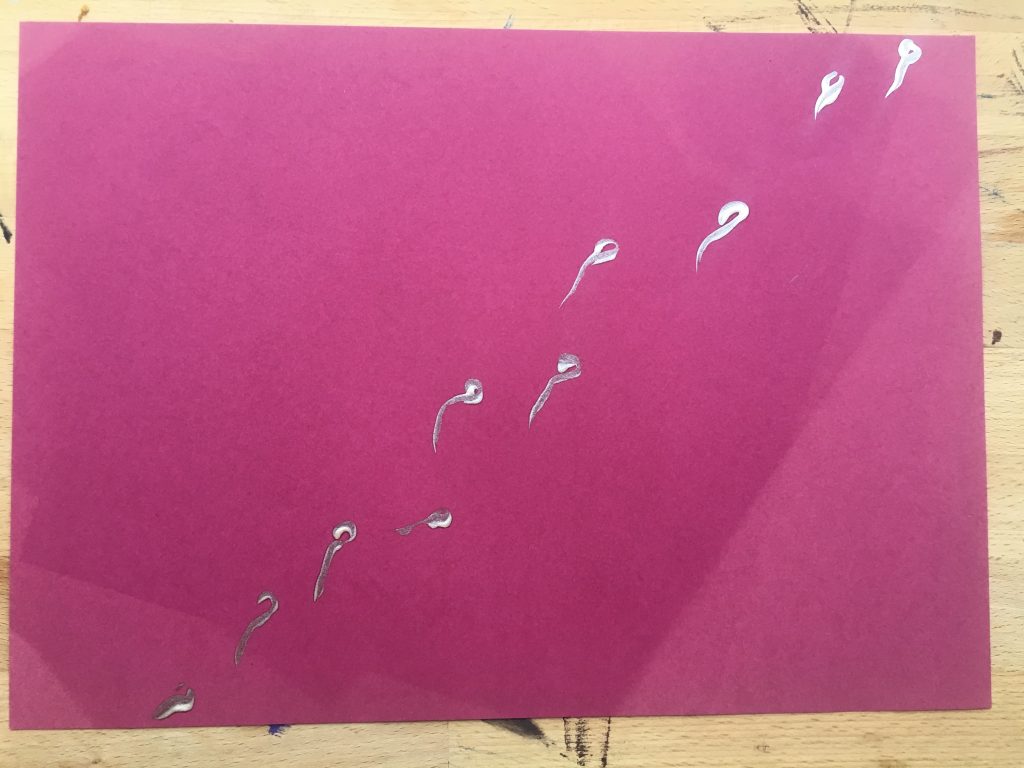

I took this as a mandate to give a sperm an eye.

Hanka disapproved. She said the eye was creepy. And also that it would be more accurate to give them noses instead.

But as sperm cannot swim as well with noses, I cut off the nose to right the chase.

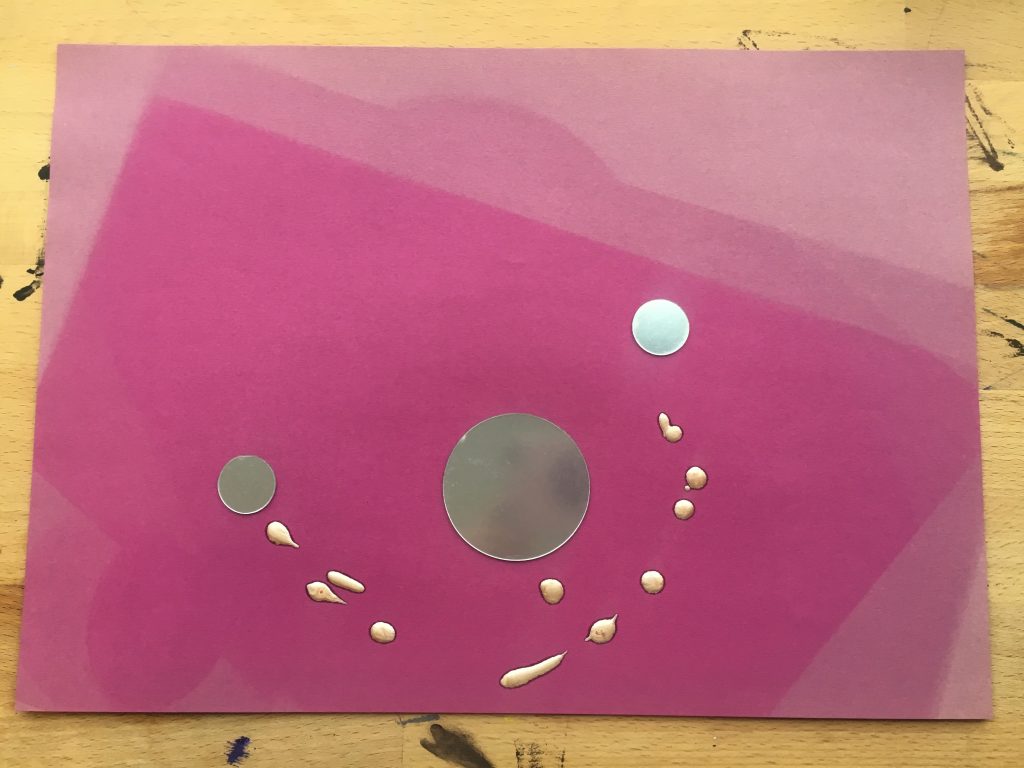

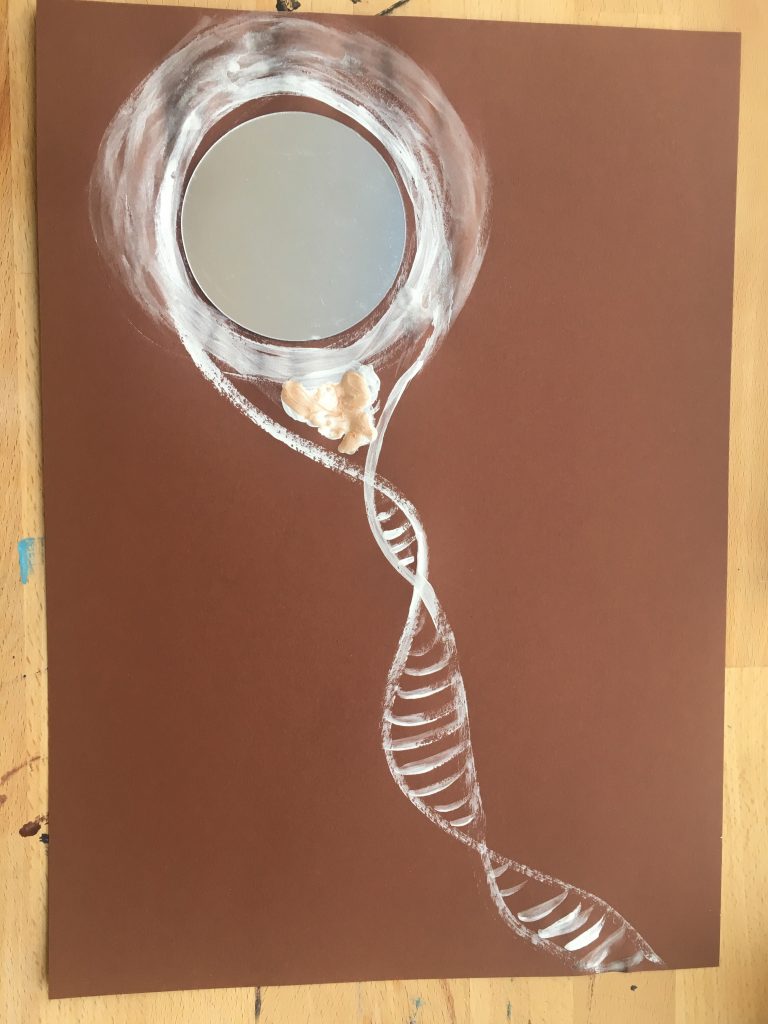

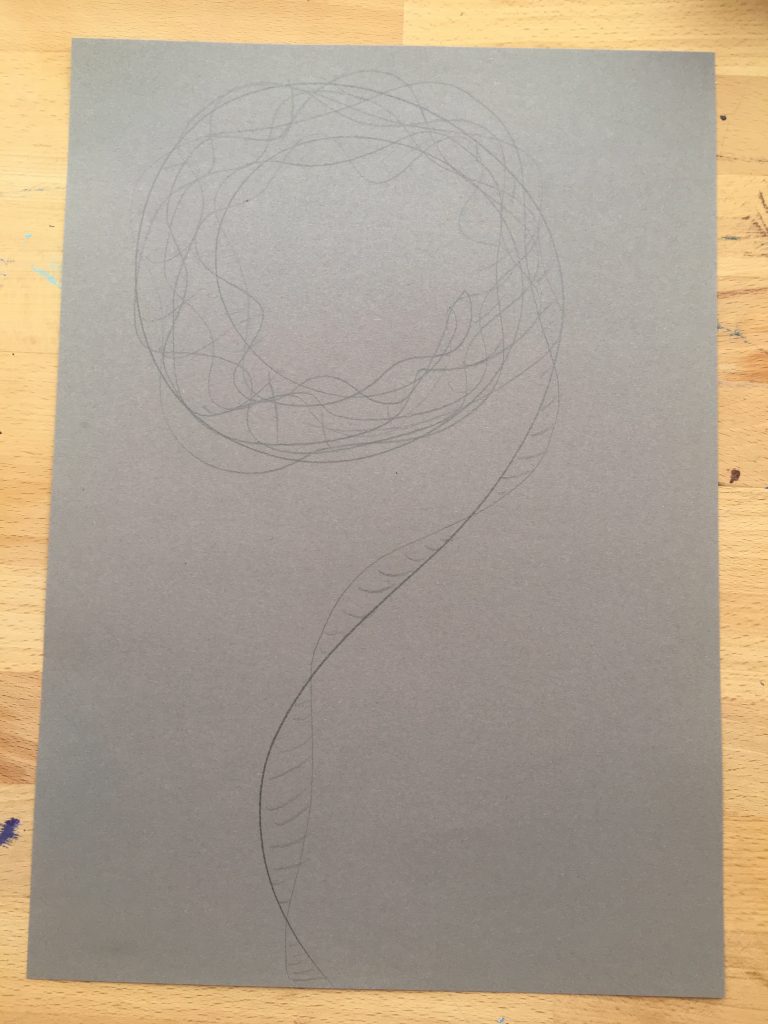

Something new and different was needed. Visions of double helices danced in my head. This may have something to do with Hanka’s recommendation of Jeremy Narby’s Cosmic Serpent, an Amazon anthropologist’s rendition of a DNA origin story, and how it jibed with what Shulgin theorized about the origins of life in TiKHAL (along the lines of panspermia and with a delightfully cheeky critique of evolutionary theory as faith), as well as the no less trippy stuff on horizontal gene transfer relayed in David Quammen’s The Tangled Tree. Hartsoeker’s error seems less quaint in light of Darwin’s.

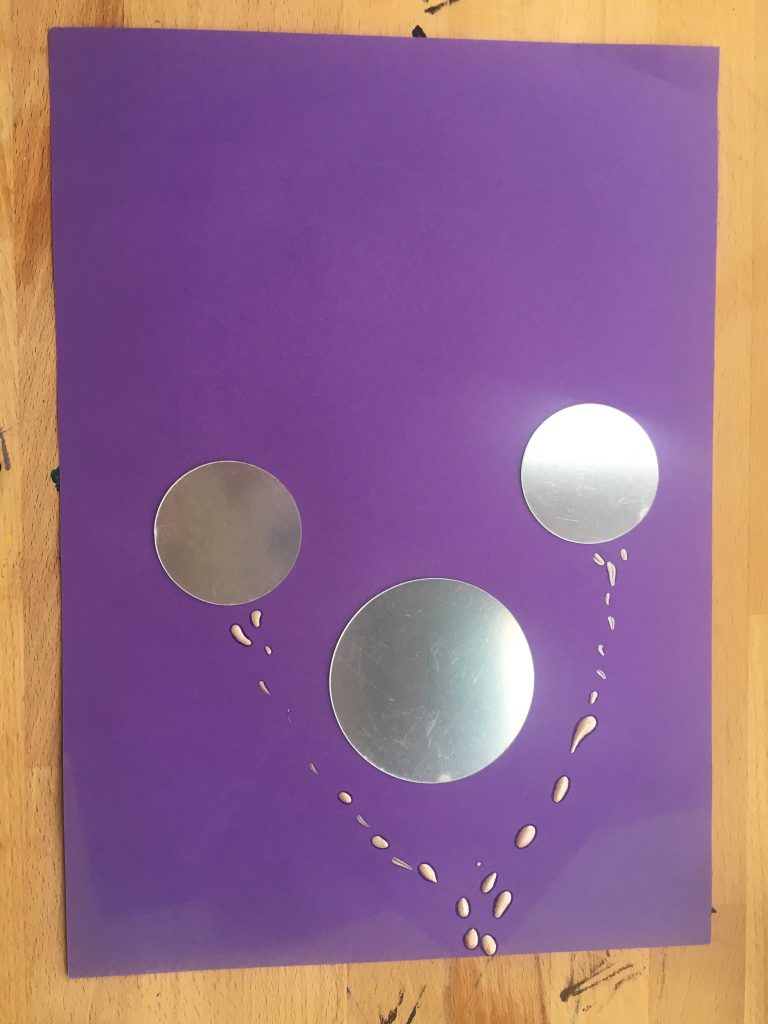

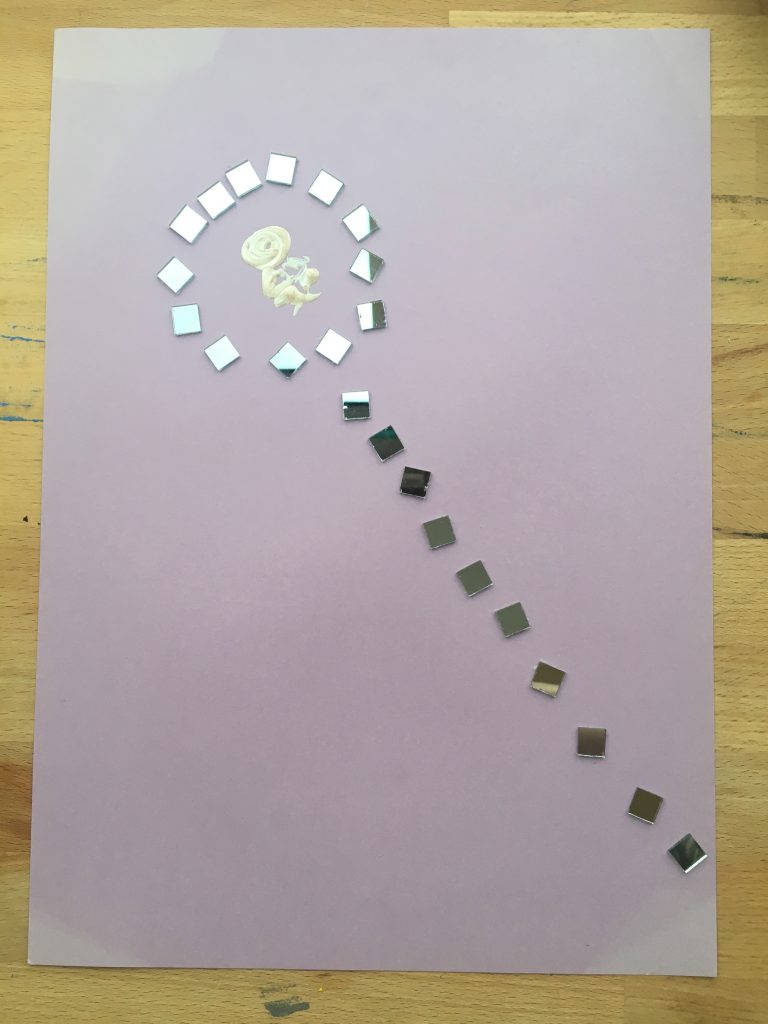

Mirrors were lying around, and the art vortex began pulling them in.

At last, Hanka liked what I made. The hypothetical homunculus had become real art. And that’s the magic of creation.