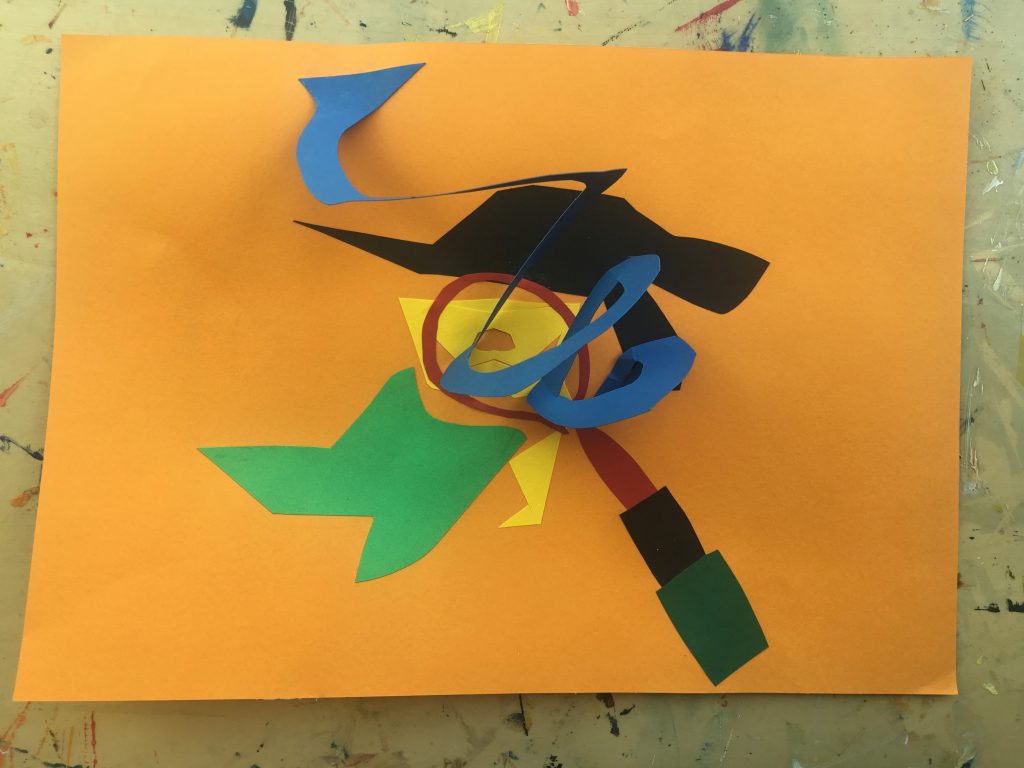

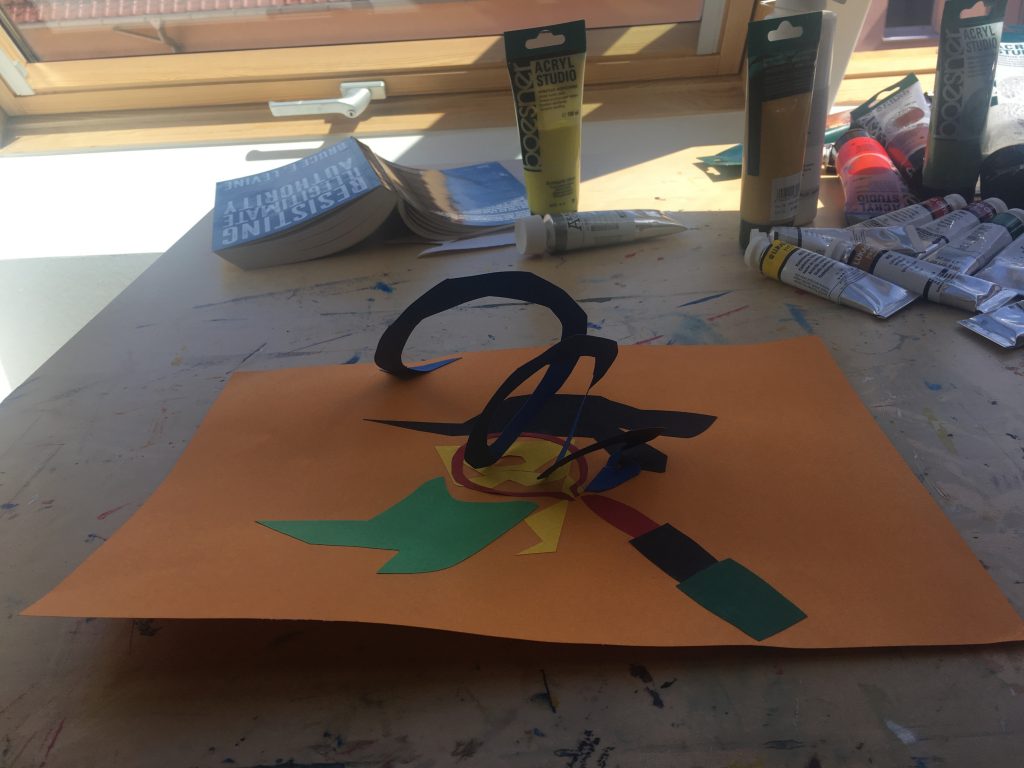

Last month I made some art in dialogue with anti-Cartesian push-back, The Anti-Cogito. Now that thinking is extended in philosophical form—Good Logic, Bad Life: Decision-Making Neuroscience Suggests AI Decision-Making’s Weaknesses, on iBorderCtrl.no.

Month: May 2019

Cosmetics

I love the idea of cosmetic x. It started with the suggestion of cosmetic psychopharmacology as a lipstick in pill form that you can put on the pig of a despairing brain:

Cosmetic psychopharmacology is not unlike cosmetic surgery. As more women get breast implants, the rest of us feel flat chested. And so it is with more women taking antidepressants and antianxiety medications. Suddenly you’re the odd one out if you aren’t like your friends, taking something to ‘take the edge off’ or give you a little lift to withstand the slings and arrows on your journey.

Dr. Julie Holland, *Moody Bitches: The Truth about the Drugs You’re Taking, the Sleep You’re Missing, the Sex You’re Not Having & What’s Really Making You Crazy* (p. 17).

Of course there’s not only cosmetic psychopharmacology, but also cosmetic psychology—a term I’m surprised it doesn’t seem anyone has yet applied to positive psychology. Positive psychology is the American-dominated field seeking to convince people with shitty quality of life in a failing empire (or two) that making gratitude lists is their salvation. (Some of its major players are known for being embroiled in contentious politics beyond that as well, to say the least.)

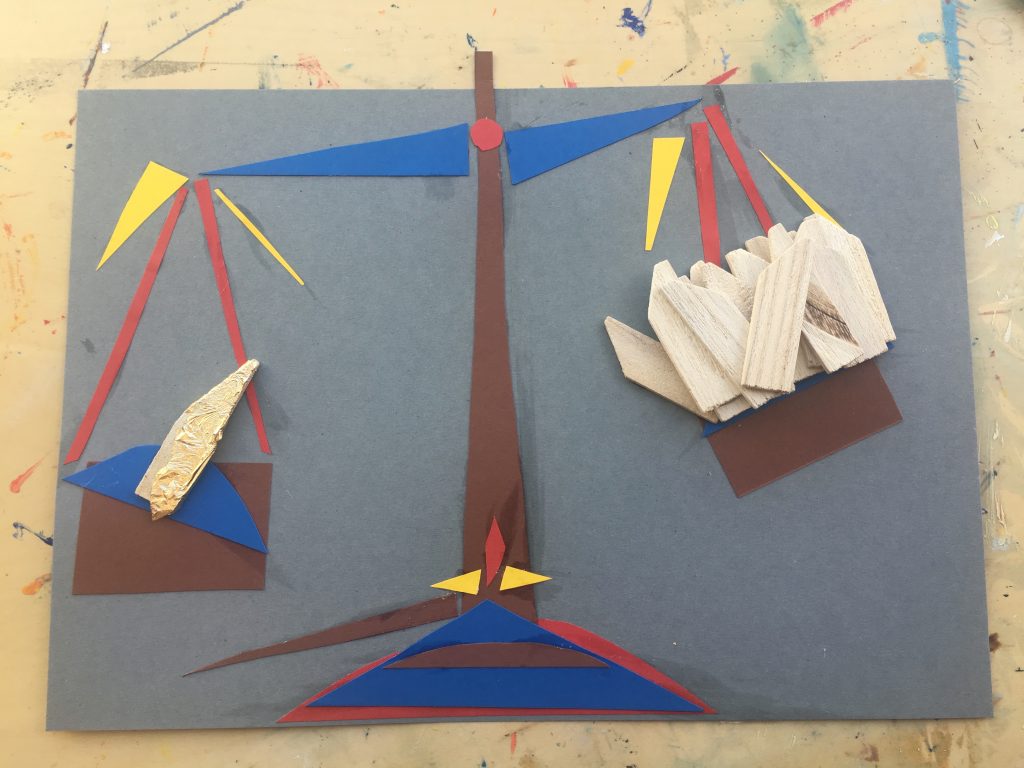

And then there’s cosmetic politics, the make-believe choice of legitimate government in a regime that is not.

In 2014, political scientists Martin Gilens and Benjamin Page, in a study published in Perspectives on Politics, empirically established how average U.S. citizens are almost completely ignored by U.S. governmental authorities in terms of public policies. Reviewing U.S. public opinions of policy issues, along with examining 1,779 different enacted public policies between 1981 and 2002, they determined that ‘even when fairly large majorities of Americans favor policy change, they generally do not get it. They conclude, ‘The central point that emerges from our research is that economic elites and organized groups representing business interests have substantial independent impacts on U.S. governmental policy, while mass-based interest groups and average citizens have little or no independent influence.”

When dissent—be it through public opinion polls, protest demonstrations, or otherwise—becomes impotent in changing policy, this is an indicator of living under authoritarian rule.

Bruce E. Levine, *Resisting Illegitimate Authority: A Thinking Person’s Guide to Being an Anti-Authoritarian—Strategies, Tools, and Models,* p. 238

You could call this form of government plutocracy (rule by the wealthy) or kleptocracy (rule by corrupt, self-enriching networks)… And you could call the elections that ostensibly validate it as somehow democratic (in spite of the evidence to the contrary), masturbation (as George Carlin does) or kabuki theater (as American pundits often do). But really the appearance of ritualized consent in the form of electoral process to legitimate fundamentally anti-democratic systems of power is cosmetic politics. It just seems more correct and less innately derogatory than the other terms. It’s not the real exercise of power; it’s the lipstick. You don’t need insults, obscure referents, or Marxist terms like false consciousness, to describe it.

And to say something is cosmetic is not innately an insult. All personification in literature is cosmetic. “I bowed my head, and heard the sea far off / washing its hands”—James Wright, At the Slackening of the Tide. “It was not Night, for all the Bells / Put out their Tongues, for Noon”—Emily Dickinson, “It was not Death, for I stood up.” And still another, all from the same source:

“The yellow fog that rubs its back upon the window-panes,

The yellow smoke that rubs its muzzle on the window-panes,

Licked its tongue into the corners of the evening,

Lingered upon the pools that stand in drains,

Let fall upon its back the soot that falls from chimneys,

Slipped by the terrace, made a sudden leap,

And seeing that it was a soft October night,

Curled once about the house, and fell asleep.”

(T.S. Eliot, The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock)

Mary Oliver, *A Poetry Handbook: A Prose Guide to Understanding and Writing Poetry*, p. 103-4.

Something that is cosmetic is on the surface and improves the appearance but not the substance—definitionally. Maybe such a thing does not really exist in people and societies though, because organisms react to stimuli (see all of Stimulus-Organism-Response psychology and physiology, e.g., Porges)… Maybe even purely cosmetic acts tend to have substantive feedback loops, and so not be purely cosmetic at all. Certainly in literature and art, the medium is the message; the surface is part of the substance in a way; and the idea of anything in poetry being “cosmetic” seems odd, like a modernist misunderstanding of why we make useless pretty things.

There is something useful in humanity, self-expression, truth that is also beautiful, the right shade of lipstick with a nice dress. Although I will be the last person to defend cosmetics in the psychopharmacology, psychology, and political contexts, I seem now to have put myself in the position of admitting (at least) that we live with them. We co-exist with those who alter appearances to maintain unhealthy and unfair status quos—and we are even, in some ways, the same. Unless we manage to actually change things.

Of course, this is only what artists and humanists always do. See a bogeyman and relate to him, and try to drag others along, too. The paradox of liberal democratic societies: accidental corporatist empathy edition…

Ioannides Extension on iBorderCtrl.no

My extension of Ioannides’ classic analysis of why most published research findings are likely to be false is live now: “Why Most Published iBorderCtrl Research Findings Are Likely to Be False,” on iBorderCtrl.no.