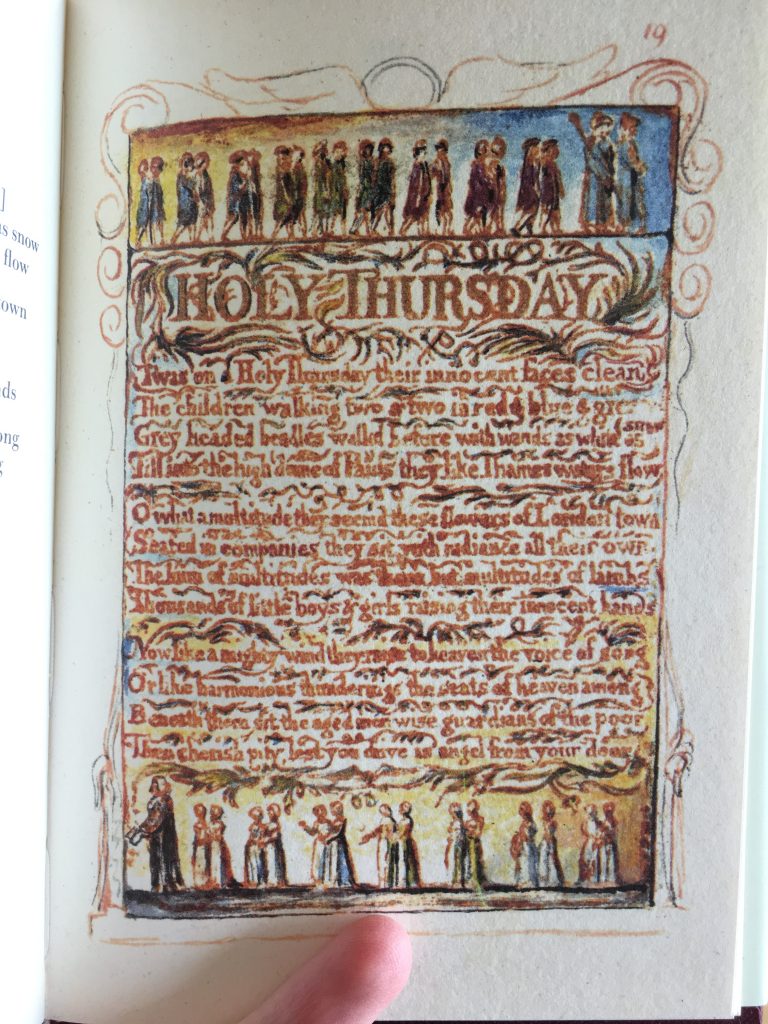

“Holy Thursday”

By William BlakeTwas on a Holy Thursday their innocent faces clean

The children walking two & two in red & blue & green

Grey-headed beadles walkd before with wands as white as snow,

Till into the high dome of Pauls they like Thames waters flowO what a multitude they seemd these flowers of London town

Seated in companies they sit with radiance all their own

The hum of multitudes was there but multitudes of lambs

Thousands of little boys & girls raising their innocent handsNow like a mighty wind they raise to heaven the voice of song

Or like harmonious thunderings the seats of Heaven among

Beneath them sit the aged men wise guardians of the poor

Then cherish pity, lest you drive an angel from your door.

Last night I ran across this poem towards the end of the Innocence half of William Blake’s illustrated poetry book Songs of Innocence and Experience: Shewing the Two Contrary States of the Human Soul, and saved it for this morning. The poem literally refers to Holy Thursday—the day between Ash Wednesday and Easter Sunday commemorating Jesus’s establishment of the Holy Communion and the priesthood at the Last Supper. But the real focus is living children, not tradition or sacrament—and the value of caring for real people as holy creatures, rather than going through procedural motions.

In the illustrated prose version of his philosophy, The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, Blake explores the compatibility of good and evil. In Songs, his use of the innocence-experience continuum to achieve that compatibility is even more explicit. One wonders whether he and Machiavelli would argue over dinner, or perhaps agree that what seems evil is in some cases merely innocence—and in others, experience.

The felt sense of their moral universes couldn’t be more different—Blake’s universe is (ultimately) kind and requires faith, while Machiavelli’s is cruel and requires cunning. Yet the political and social contexts of their writings share striking similarities. Machiavelli was keen political analyst, republican consort, and Medici torture survivor who explicitly wrote The Prince for the family responsible for his torture to systematize tyranny, while resisting between the lines—often showing rather than telling why free republics are better than corrupt principalities. Blake, friends with his own notable radical contemporaries including Tom Paine and Mary Wollstonecraft, survived charges of high treason and a sedition trial that contributed to his failing health. Both see continuity and freedom where others see sharp difference and constriction. Both proposed a marriage between heaven and hell, but Blake saw himself as observing and celebrating the infinite, bursting with meaning and worth—while Machiavelli saw himself as observing and stating the obvious, dictated always by power.