I’m a Thanksgiving baby (Sagittarius), I read Rob Brezny’s Free Will horoscopes even though I know that’s ridiculous, and he gave us a writing prompt this week that this post responds to…

Review: In Vera Wilde’s “Life,” It Could Happen Here

WTF Critics’ Pick Drama, Play, Self-Creation Closing Date: TBD Berlin

The Cold War has returned to Berlin, with the heat to make McCarthy hard. This time, crypto is the new red. The new cold warriors are the hot freaks and geeks of the global anti-surveillance resistance—WikiLeaks, Cryptoparty, Tactical Tech, and the other five openly swinging LGBT independent journalists in the world.

Gone is the tentative touch of previous casts, detrimental in particular to the Charlottesville, LA, and Boston runs in 2014-5; one senses the director is confident, competent, and demanding of the actors’ whole presence. This production is thus able to build on the best of prior runs, first and foremost the prolific painting, gentle music, light poetry and other expressive merits of the original.

Reflecting the same iterative nature of the effort, previous criticisms of Vera Wilde’s “Life” abide: a synesthetic creative process and multiplicity of possible narratives leaves the work feeling scattered; perfectionism gets in the way of experimentation—with swift social sanction when it doesn’t; and the ability to play with different lenses of viewing self and other, though distinctly improved in this most recent Continental production, remains spotty. Absurd, long-winded, and self-referential, “Life” yet offers much to the critical observer who stays with it.

The plot, though fresh with digital-age details, echoes witch-hunts through the ages. What’s fresh here is the flashback nature of disclosures, and (sadly) the gender of the protagonist as a political actor. It’s clearly still hard for Vera, once silent for months, to physically speak on occasion; nearly impossible to sing; and difficult to say who she is and what she’s done. But watching her increasingly embrace the simplicity of being a young artist living in Berlin helps make real the promise of a free and happy future for individuals who choose it, though the world may burn.

But part of the artist remains the Harvard scientist, thoughtful interviewer, and innocent interrogation subject who came before. Faced with evidence that some of the abuses she documented were not lone cases, the scientist turned over years of documents, sources, and other research to a reporter—who relied heavily on her contributions without offering the already-harassed researcher a potentially protective byline. It was dangerous for sitting Senators and their staff to document and denounce the CIA breaking the law and lying to Congress about it; it was suicidal for a graduate student working alone. Could it be worth it to lose your country (job, career, home, friends, pots and pans and paintings…), to gain your soul?

Love her or hate her, that woman had more balls than Donald Trump in a playpen contest. And the few mentors who knew told her to hide the brave thing she had done, as if to protect her. It is she, not they, who learns that silence does not protect you in a police state. Nor does changing your name and moving across the country a few times. And collaboration does not protect you either, if you insist on telling the truth—as Vera finds out when she drinks her police research colleagues’ procedural justice Kool-Aid, and behaves as though rule of law applies and one may be permitted surprise when its proponents fall short.

As a lie detection researcher, the artist currently known as Vera established that federal agencies that use polygraphs do not seem to behave as though equal opportunity law applies to their polygraph programs. Vera documented multiple cases of agencies including the CIA undermining the war on terror and breaking equal opportunity law in polygraph interrogations through questioning about religious and political belief, sexuality, and even sex crime victimization—while denying applicants and employees recourse to EO complaint procedures. She also released documentation that the CIA lied to Congress about that practice, after unsuccessfully suing multiple federal agencies for a statement of policy or practice on the applicability of EO law to polygraph programs—and data to test the programs for bias. Just cos they won’t say, don’t mean she gonna go away.

Of course the real polygraph story is, as usual in the era of Snowden and Panama, that what you’d assume is illegal cos it violates rule of law and decency—like interrogating people about their faith or sex—is formally legal under the current regime. But it’s interesting how badly agencies like the CIA don’t want to have to make that argument explicitly—to the extent that they’ve lied to Congress to avoid it. Lying to Congress is still illegal, but apparently not if you’re the director of national intelligence or the head of the NSA, or the CIA.

It was phenomenally stupid to blog about that as a penniless postdoc—as if she honestly believed the feds would follow the law, and police and colleagues would protect her if they didn’t. Despite that permanent naivety, sometimes the protagonist seems quietly courageous in this political context—as in her personal choice to go someplace new, trust her intuition, find love and let it in.

And sometimes, Vera seems like a derivative, second-rate Heidi—chronicling her adventures for no one in particular, worrying instead of doing, daring like a man before purring in a puddle on the floor, just another thirty-something waif who can barely hear the phone ring over the ticking of her own biological clock. Much to the consternation of her non-breeding partner. But if winning is simply getting on with it, she’s triumphant in her painting, cooking, loving extravaganza—making home not war.

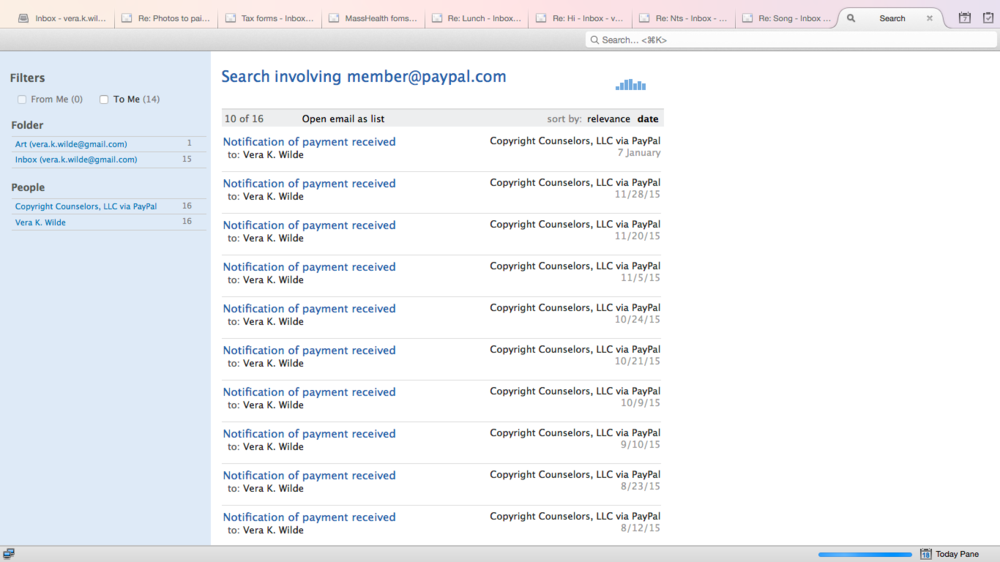

Still, it’s not all celebration and self-deprecating humor. Citibank has kept funds from a closed account, PayPal appears to be routing all incoming payments through a CIA network-associated lawyer’s company, U.S. T-Mobile seemed to reroute calls attempted domestically and internationally to a scam cruise line, an unknown party created a website with plausibly relevant (and sexually explicit) content under her old name, and even the cabbies in Boston seemed to be in on the joke. This is overwhelming force on a level that is literally unbelievable. Yet, parts of Vera’s wild story begin to seem slightly more plausible as more information trickles out, as when FOIA requests reveal the use of undercover “cop cabs.”

Combining oppressive surveillance (or the use of obvious surveillance to harass and intimidate subjects), sockpuppetry (or the use of fake in-person and social media personae to mislead, threaten, and even deprive subjects of sleep), data and device compromises, national security journalists and lawyers who refuse to use encryption on request, mentors who throw whistleblowers all the way under the bus, and other forms of threat, intimidation, and fraud, the police state hands the cute little postdoc her ass on a silver platter.

But what seems from the first person like an overwhelming experience of illegal retaliation is also clearly indistinguishable from insanity from other perspectives. Such ambiguities are not coincidental; Stasi and Soviet psychological operations were designed to discredit political opponents by causing them to appear unstable. Unsurprisingly, then, “Life” has too many mysteries to be explained wholly by corporate-state collision to crush dissent.

Yet this, too, points to universal truths the production draws fellow-travelers into dancing with around a campfire. The nature of trauma is that the better we can communicate about it, the less power it has over us; traumatized people can’t convey the context of their behavior, and powerful storytellers—who don’t need to tell their own stories anymore—are already healed. This is why it is heartbreaking but unavoidable that no one ever shows up when you need fight, flight, or friends.

At a political level up from that interpersonal experience of the paradox of trauma narrative, crazy conditions tend to drive people crazy; and plausible deniability about the creation of those conditions is an art of the powerful. Neutrality is increasingly fraught, and so science can easily be a form of collaboration in such a world.

Perhaps this is why Vera’s attempt to return after a year’s hiatus to her academic work, by presenting alongside a global lie detection expert at an American Studies Symposium in Japan, must fail. She prepares and presents well, after nursing a stress migraine through tears on the plane over—and then stays up sobbing hysterically all night after the job is done.

Her vulnerability to lawless retaliation in U.S. client states and international airspace hits her through flashbacks of the retaliation that caused her to leave the States—as does her own powerlessness to communicate such vulnerability. And of course the academics don’t think she’s doing scholarship because she’s not pretending neutrality means stating the facts and throwing up your hands. Upon returning home, she falls asleep safe and warm, only to wake up drenched in sweat, having imagined that her harassers hacked her devices and threatened her family. The irony of being yet more vulnerable in some senses when you have loved ones and are loved, instead of facing evil utterly alone, is bittersweet.

In spite of such backward leaps, in the fullness of literary time, we see resilience through creative drive. But at the same time, the ways in which everyone seems to be in various stages of recovery from trauma troubles the notions of resilience and resistance in the context of totalitarianism. When artists and intellectuals are forced into a false choice between being crazy and being collaborators, what hope does society have to shelter free thinking and expression?

Perhaps it has none. Even so, “Life” insists, individual free thinkers may find and love one another while the empire slowly crumbles—trying, and increasingly failing, to crush its own last, best hopes along the way. To simply walk away and begin again, again, when things are not right, remains quintessentially American.

But the long arc of history bends toward a weird sort of chiasmus, as refugees from imperial degradation of rule of law gather in the same city they once fled. And so what could read as a cautionary tale about attempting to do independent police research in a police state, instead comes across as a heart-warming tale of finding home in strange places, asserting self with the grace of safety, and above all being excellent to one another in a dangerous time. It’s a wild world. And it’s full of love and beauty, and soul-mates gazing up together from the gutter to the stars.

Vera Wilde’s “Life” runs in Berlin as long as the city grants freelance artist visas to catch brain drain. Get a passport.