Since my business idea is getting bigger rather than smaller, I’m trying harder to make myself go outside to validate it before writing a business plan, or seven. This led me to East London yesterday to talk with people about ISIS.

Experiment

Designing effective validation experiments for a business idea is just like designing experiments to test any other idea. It involves four elements:

1. Hypothesis: Client (moderate person) has problem combatting extremist group recruitment online. This applies to all hate groups with online presence, the best organized of which is ISIS/ISIL.

2. Riskiest assumption: Peers would respectfully, effectively contest extremist narrative if they knew who, when, and how to target online communications to at-risk community members.

3. Method: Interviews, pitch, concierge service, in that order.

4. Minimum criterion for success: I expect 6/10 East London moderate Muslims to indicate IS online radicalization is a pain point—a significant problem they worry about—and they’d use a tool to address the worry.

Result

Wrong.

Responses fit into the following five categories:

– Talk to someone else

– Be afraid, be very afraid

– Don’t you know 9/11 was an inside job, the U.S. is arming ISIS, and Russia is going to nuke you personally for trying to police the world?

– They are already surveilled, won’t this feel like more targeting? (From white secular people, ironically lumping all Muslims into one category but making a good point nonetheless)

– Take it offline, talk to people, get people into more positive cross-cultural dialogue and experiences through orthogonal stuff like music

Things it was suggested people want that would make better business ideas than “world peace through art”:

– Food

– Housing

– Rides

– Ways to make more money

– Art lessons

Lessons Learned

First, the framing makes a big difference. “Combatting online hate group recruitment” is different from “defeating ISIS with art.” The former sounds dainty and academic to me, while the latter sounds exciting. But no one else likes the latter, so I should probably stop saying it unless I can get a few million dollars to make pop-up divine art to freak out foot soldiers in Syria. (But if you have a ton of gold leaf and combat experience, call me.)

Second, the cognitive stickiness of conspiracy theories is really important. We’ve known for a long time that majorities in several Muslim countries don’t believe Arabs are responsible for 9/11. And the alternative theories tend to involve powerful conspiracies, like the U.S. Government, Israel, a global Zionist conspiracy, or whatever.

It’s a lot less comfortable to believe that there is no man behind the curtain. The contemporary analogue of Hannah Arendt’s Eichmann in Jerusalem—the embodiment of a boring villain, arguably a bureaucrat in a bad barrel more than a bad apple per se—is just as much a teenager on Twitter recruiting for ISIS as it is a faceless bureaucrat enforcing equal laws with unequal consequences. Sometimes, I think we have so much power with social media, democracy, and the market that Eichmann is all of us. If something is wrong and we don’t right it, whose fault is that? It doesn’t help to blame ourselves, but we’re empowered to change things.

Anyway, you can use this cognitive-stickiness-of-conspiracies knowledge by pointing out how much sense it would make for Russia to support ISIS—a godless foe using other people’s perceived superstitions to destabilize an oil-rich region and hobble a competitor superpower. One could envision a whole social media campaign having fun with that.

But it makes more sense to focus on the bigger picture of why conspiracy theories are so sticky and how to change the focus of the discourse about crime and security, war and peace.

The bigger picture looks something like this:

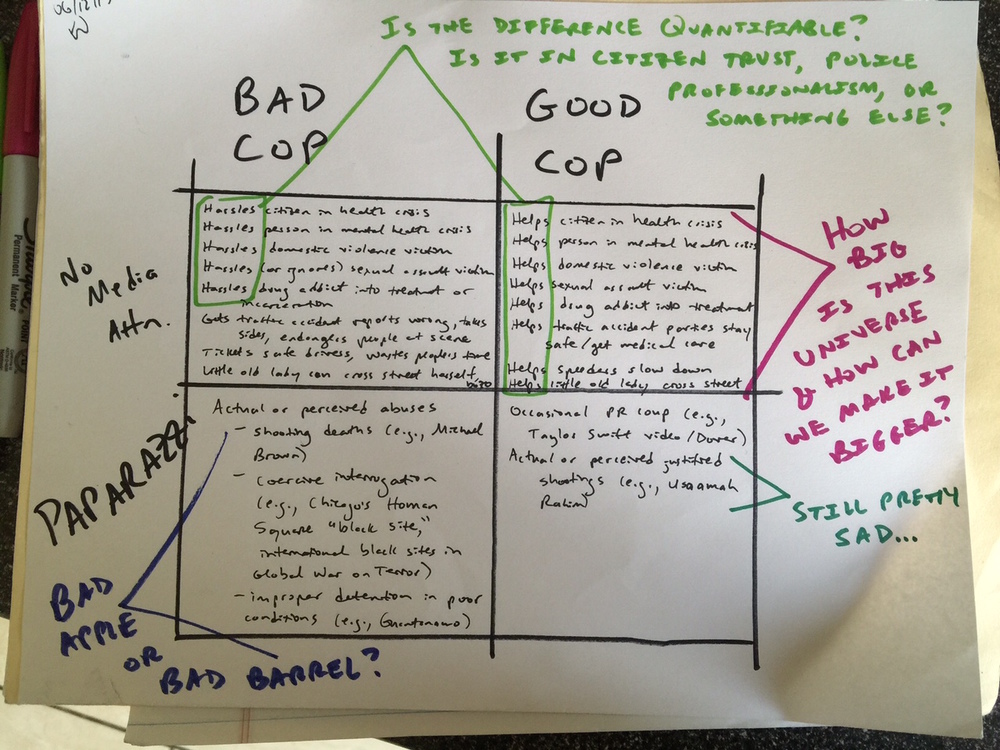

This is a very rough application of Bayes’ rule, which says that weird people are weird. Subgroup membership matters. In security, it means that bad cops are going to get a lot more press attention than good cops as a general rule. That’s a problem for security itself if procedural justice research is right that perception is reality, trust creates security and mistrust breeds lawlessness.

The universe of media attention and policing can be broken up into four categories—no media attention for bad cops, no media attention for good cops, media blitz for bad cops, and media blitz for good cops. Most of the good police work is not going to get media attention, in part because of privacy protections, as I’ve written about before. And it’s non-obvious what distinguishes good from bad policing—police helping versus hassling people—in the majority of police interactions, in the first row there. Is it in the trust or mistrust a person already has of police in general before a particular interaction takes place? Or the tone of voice and language police use, their professionalism or personality? Or something else?

Community-oriented policing research tends to suggest it’s all of the above—but who cares? These universes of the majority of policing aren’t what make the news anyway. Those paparazzi boxes, in the second row of the Bad Cop-Good Cop table, are more heavily populated by outliers, or statistical anomalies. Minority occurrences make up the majority of reporting on policing.

Which is not to say they’re unimportant! Abuses are horrible and should be systematically reduced through institutional reforms that make better barrels as well as investigations that identify and punish bad apples. It’s just the context of the media environment. And it has its own consequences. Namely, it undermines the public trust that makes people more law-abiding and thus makes communities safer.

Third, people seem pretty unhappy with the state right now because of the stuff in the bottom left box. There’s a lot of anti-surveillance backlash, protests against actual or perceived police abuses, and the like. But there might not actually be a market demand for security services like combatting hate group recruitment on social media (a.k.a. defeating ISIS with art). Maybe Hobbes was right that the first responsibility of the state is to provide security for its citizens. And maybe that provision is something that the market delegates to the government precisely because no one wants to pay for it individually, but we all need it collectively to do anything else.

If that’s the case, this explains why calls by people like Representative Cory Booker—for a better entertainment/arts industry response to ISIS radicalizing our young people on social media—seem to be failing to mobilize an effective response. Industries respond to market demand, and the market doesn’t get Bayes’ rule. So people who care deeply about truth and justice are more easily mobilized against security forces and in favor of the perceived underdog—doubtless a solid moral intuition in lots of cases. But not when the security forces actually are generally law-abiding and the underdog has a dirty bomb.

Police mistrust creates a tragedy of decontextualized moral intuitions. People mistrust government for lots of reasons, many of them independent of the police or security forces—it’s kind-of an American tradition. But if the market isn’t going to make us safe—we need government for that after all—and government is too centralized to deal with the doubly decentralized threat of terrorist recruiting on social media—we have a problem.

I was hoping my experiment would bear out market demand for a website and/or app to decentralize, localize, and make a fun art game of the response to extremist recruitment on social media. I was hoping it would show how Usaamah Rahim’s death in Boston last week could have been prevented by ordinary people using ideas to combat ideas before police felt compelled to use force to prevent a radicalized person from using force. Maybe I was wrong.

Or maybe I need to use different language, talk to younger people, and ask for help on the Internet.