In a week, I’m putting all the lovely original oil paintings on my online gallery in storage. So if you’d like to buy one to support my life experiment in making art and traveling, now’s the time to visit my Etsy store.

After that, you can still get art swag at my Zazzle store. Or turn up Ringo and ask me to paint you a postcard.

I’m perversely excited about all the mistakes I’ve made in just a few months of attempted business launches. Better to fail earlier and harder, and learn, than not.

Had I not gotten super cool-looking—but statistically insignificant—results in pilot testing for my dissertation research… That everyone I talked to was sure would pan out—but didn’t… I might have gone in a different direction… And not been crushed when the initial results turned out to be wrong.

Had I not gone along to get along in relationships for many years, I might have started asking for what I want sooner.

Abject failure can generate better outcomes than early, middling success.

And boy have my initial business launch attempts failed. Here are three things that seem to have gone horribly wrong—and how they underscore what has gone terrifically right.

Horribly Wrong Sequencing

I quit my job before monetizing my business.

Don’t do that.

Unless of course you’re called. And then accept that your sequencing will look screwy to everyone else. And you will figure out what is next as you go, because you are showing up to what is next in your own life, on your own time.

Horribly Wrong Investing

I invested five figures in launching my business. Before adequately testing the business model.

Don’t do that either.

Unless of course you’re trying to figure out how this business thing works. And then accept that risk is part of the game. And a lot of apparently successful businesspeople actually lose more than they gain. Risking and trusting are integral to producing better individual and aggregate outcomes. As long as you listen to the outcome of the risk, and adjust.

Horribly Wrong Goal-Setting

I tried a bunch of different goal-setting exercises, like Napoleon Hill’s autosuggestion and Tim Ferriss’s dreamlining. There are a million different forms of the same basic exercise here. They’re all about directing positive selective attention to actualizing what you really want. Which requires first knowing what that is. And figuring out what you really want is actually a LOT of work.

Do that.

Throw it away. Do it again.

It’s hard. We’re all looking for the golden ball in Robert Bly’s terms—which is an allegorical way of saying we all lose touch with something, maybe just by being born, maybe by growing up (or trying to). And knowing what we really want is part of getting back in touch with a certain holiness, so we can get it.

How Three Wrongs Make Right

A lot of failure in asking—for painting sales, publications, editing clients—has desensitized me to the horror of it. This increased comfort with failing enabled me to sing my own songs on the streets of Mexico despite barely being able make noise in my own apartment sometimes. It enabled me to ask my housing lawyer to get my damages back from the great Cambridge bedbug imbroglio of ’14 (don’t ask)—or file in district court already, because it’s been eight months and that little mess tanked my meagre savings. (I’ve been asking nicely and sleeping on a sleeping bag since September. It’s like a little camping party in my apartment.)

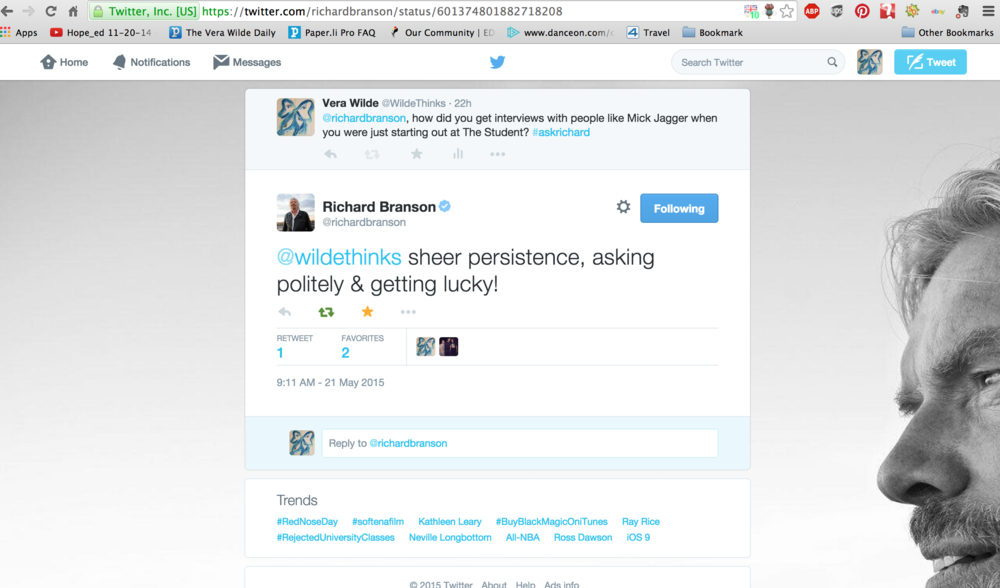

And it enabled me to ask Richard Branson for advice on Twitter.

He answered.

This is brilliant. This is right. I still haven’t figured out quite how to apply this to my own goals. Simple is hard.

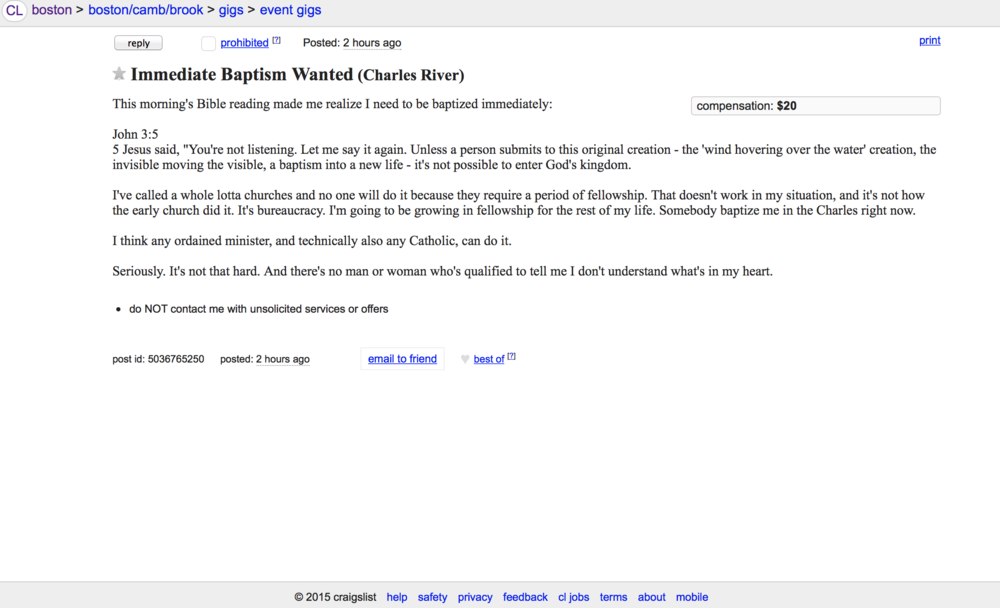

I also still haven’t gotten baptized—a goal for the day—despite calling over a dozen churches. SIMPLE IS HARD.

But I’ll get it. Because I know how to ask for what I want. Politely. Persistently. And I’m doing it.

More importantly, I’m figuring out how to ask other people what they want. Systematically. So I can give them what they need and profit from helping them.

Just like research turned out to be much more about learning what I didn’t know I didn’t know, than testing my original hypotheses—which were almost entirely wrong—so too business turns out to be much more about learning what problems I can solve for people for fun, that I’m not even sure they should pay me for because I love doing this stuff… That asking, listening, changing, asking again, listening, changing, asking again game that vocalists play with accompaniment in improv, and radios can play too. It’s all chaos. It’s all good. That’s how social exchange works—decentralized, unpredictable, fluid, and better than anything you could imagine before showing up to play.

It’s basically the Bill Murray of business planning. Show up. Do what people need. Have fun. Poof. “No one will ever believe you,” but you better pay taxes on it anyway.

At least that’s what VERY preliminary results of my first market tests show. More about that soon.

Making the time to prioritize your own work, spending money like you believe investing in your dreams is a good investment, and articulating exactly what you want like it matters and you can get it aren’t mistakes. They’re steps. Just like any failure.