Lie Detectors On Trial?

Science, Security, and Accountability in the Era of the Hague Invasion Act

By Vera Wilde, P.h.D.

American Studies Seminar

Osaka University

19 March, 2016

Ken Alder’s work stands as the definitive history of lie detection as an American obsession. Scholars like Richard Leo in his work on police interrogation and Jack Balkin in his work on the surveillance state have echoed and extended Alder’s arguments in the contemporary American context. The main point I want to make in dialogue with this body of research is that of the global political significance of lie detection as a case study. The continuing growth of lie detection (aka polygraph; verbal, behavioral, or physiological deception detection; and credibility/threat assessment) programs illustrates how corrupt elites tend to capture the political process, and thus the power and money it controls—without regard for science. The ways in which these programs hurt the thing they ostensibly help—security—illustrate why political corruption is a global collective action problem, a security problem no less, of existential proportions.

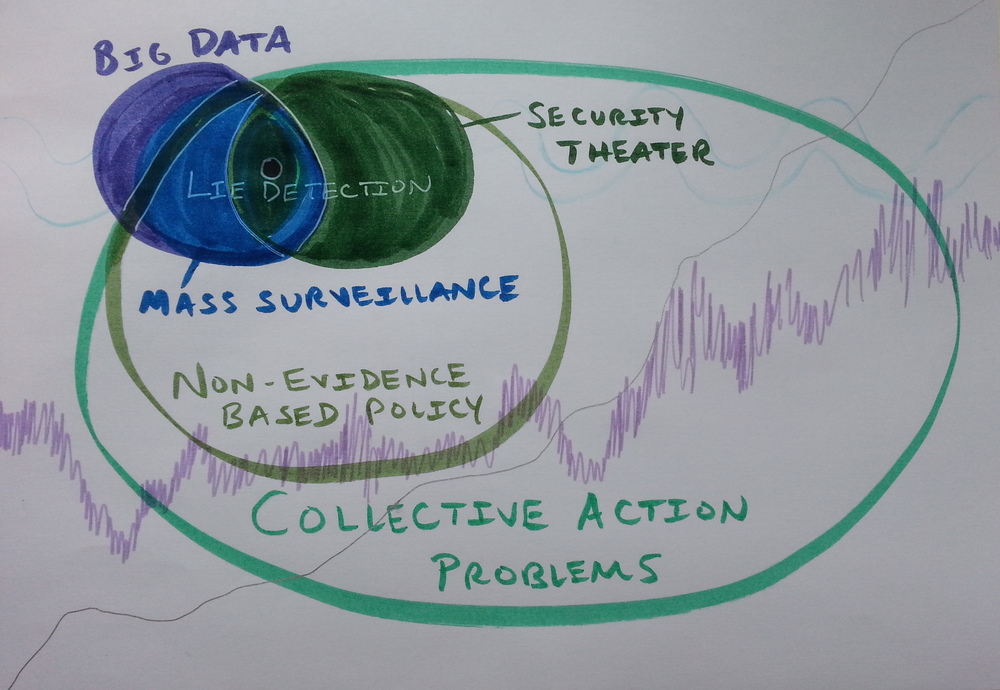

Lie detection is one case study[1] at the intersection of the subset of Big Data phenomena popularly known as “mass surveillance”—defined as mass screenings for low-prevalence problems—and the subset of security procedures known as “security theater”—or security measures that enhance perceptions that security measures are being taken rather than enhancing security itself (National Research Council, 2003; Schneier, 2006). Big Data is growing. More everyday “smart” devices, browsers, search engines, other online services, and cookies in emails, ads, and websites, log more personal information that is in turn re-bundled and sold as a product to companies that want to use it to better predict behavior ranging from solvency to crime. As Big Data grows, this intersection between mass surveillance and security theater becomes more and more important for ordinary people’s life chances.

If the credit rating company, for example, incorporates data from your browsing behavior in its calculation of your financial well-being, that might impair your ability to obtain a credit card with a good interest rate, or a home loan. Those conditions might in turn hurt your future credit rating by stacking the financial institutional deck against you, thus generating a self-fulfilling prophecy. Similarly, if the border guards incorporate data from your pupils, sweat glands, and cardiovascular system into their calculation of your propensity to do something evil when they let you through a checkpoint—as Frontex (European Union border guards) recently did in collaborative field testing with American researchers working on a next-generation lie detector called AVATAR (Automated Virtual Agent for Truth Assessments in Real-time)—that might affect your freedom of movement in a self-fulfilling sense. For example, a false positive AVATAR flag might cause you to undergo a secondary search that otherwise would not have taken place, turning up contraband such as weapons or drugs (BORDERS National Center for Border Security and Immigration, 2013).[2]

In cognitive psychology, we might talk about this kind of feedback loop in terms of selective attention—you tend to find what you’re looking for or thinking about. In social science more broadly, we might call this selection bias. In research design, we try to minimize selection bias by triangulating data sources and analysis types, ideally combining observational data for its high external validity in the sense of low artificiality, with experimental data for its unique abilities to potentially pinpoint causation and even causal mechanisms. The gold standard of research design in public policy thus tends to be field experimentation. But well-designed field experiments in lie detection pose special ethical and logistical problems: the stakes must be high, the lie detectors hypothesis-blind, and the experimenter must have some way of determining what polygraphers call “ground truth” absent the existence of an actual lie detector. Of course, the point is moot because most companies and governments are bad about running field experiments or otherwise doing evidence-based business and governance—more on this later.

[Table 1 here: Results of polygraph interpretation assuming better than state-of-the-art accuracy in a hypothetical population of 10,000 people including 10 spies. Modified from National Research Council 2003. See “Growing National Security Threat from Growing National Security Programs,” V. Wilde, 2015.]

The main reason lie detection and its next-generation attempts to better predict future behavior consistently remain security theater, as opposed to science, is that they tend to generate a large number of false positives while also generating false negatives. Here, false positives are cases where someone innocent gets in trouble, false negatives where someone guilty gets away. The balance of these types of cases is a matter of Bayesian statistics. The U.S. National Academy of Sciences showed how this plays out in their 2003 Congressionally commissioned review of the scientific evidence on the polygraph. Table 1 shows how NAS applied Bayes’ Rule—a mathematical theorem about how weird people are weird—to polygraph screening with a better than best-case accuracy rate of 80%, to identify spies at a higher than worst-case occurrence rate of .1% in national labs. Based on the math, they concluded that one type of mass surveillance—polygraph screening programs of all lab employees (mass screening) for espionage (a low-prevalence problem)—backfires and degrades the security it purports to enhance. Mass surveillance makes the haystack in which the institution searches harder for possible needles quite large, while still missing some needles. The solution is not to build a bigger haystack. In this sense, Bayes’ Rule illustrates how optimizing, or going for perfection, can underperform satisficing, or accepting error as inevitable and investing limited (cognitive and other) resources in areas other than minimizing it (Simon 1972).

The fact that mass surveillance hurts national security may come as a surprise to the ordinary citizen who expects governmental policy to do what it says it does, and hears typical media discourse pitting liberty and security as if they are opposed rather than congruent values. That opposition miscomprehends the political significance of Bayes’ Rule. But most political historians, policy analysts

, and social science experimentalists agree that most governance is not evidence-based in any meaningful sense.

In the U.S., leading 20th century social science methodologist Donald Campbell argued for an “experimenting society” in which researchers would collaborate with bureaucrats and law-makers to implement policies using field experimental and other methods that would tell us what worked, better than the anecdata and observational data we had ever could (Campbell 1998). Campbell’s call fell on largely deaf ears. Instead, science is politicized more than politics is evidence-based. For example, the National Science Foundation recently canceled a political science grant cycle due to concerns about complying with a federal law forbidding NSF funding for political science research that is not vital to national security or economic interests. Meanwhile, the bureaucrats and legislators responsible for that very requirement do not have to try to measure the effects of their policies and practices (Mole 2013).

We constantly miss opportunities to even roll out mass policy changes, such as the increasing adoption of police body cameras, in a staggered way permitting randomization in a form of quasi-experimentation. In the case of body cameras, the Congressional Research Service recently identified a number of implementation issues that researchers could have formulated as hypotheses to field-test in jurisdiction-matched quasi-experiments, improving the science behind police practice while changing when and how—not whether—more and more police agencies adopt body cameras (Feeney 2015, James 2014, Mearian 2015). But lawmakers, researchers, and police leaders, faced with a lack of political scientific infrastructure and many competing demands on limited time and other resources, missed that opportunity.

In the bigger picture, America is the worst offender in policies without scientific basis. The U.S. is a massive global outlier in its defense spending—in the absence of proof that this spending makes us safer, especially as compared to an alternative use of finite resources (e.g., SIPRI Military Expenditure Database 2015). But no country on earth does evidence-based policy in the way Campbell envisioned. Policy change is difficult, and science does not generally drive it (Pielke 2007). Much like liberty and security, there are no absolutes here—only more or less free and safe societies (for various values of free and safe), and more or less evidence-based governance.

Yet, governance that is not evidence-based is not only irrational in a homo economicus sense. That is, in liberal democratic social contract theory (e.g., Hobbes and Locke), citizens pay taxes to legitimate governments in order to fund protection of their limited natural rights to life, liberty, and property. Paying those taxes to fund security programs that backfire, or are unproven and not structured in such a way that they could be disproven, is not something the fictitious rational man would do. Beyond that unsurprising failure of real people’s behavior to conform to a fictitious standard of rationality in a fictitious story of what makes governments legitimate political entities—as opposed to relatively effective organized crime syndicates (Tilly, Evans, Rueschemeyer, and Skocpol, 1985)—there are very real consequences for the public good when special-interest groups can capture massive resources with impunity. It’s bad for national fashion when Big Tailor can sell the emperor lots of expensive new clothes.

Similarly, it’s bad for national security when self-anointed security experts like lie detectors can sell the federal government lots of expensive new programs—as they did with unprecedented success following the September 11, 2001, terror attacks (e.g., Priest and Arkin 2010). For instance, polygraph screenings rose nearly 750% in the FBI from 2002 to 2005 (U.S. Department of Justice, 2006). The pattern of this success illustrates the difference between irrational, non-evidence-based governance, and actively bad governance. Irrational governance is normal. People are irrational (Tversky & Kahneman 1981), and sometimes that quality is functional in democracies (Kuklinski & Quirk 2000). Corrupt governance is pathological. This pathology is ironic, or the opposite of what might be expected, in four realms: international corruption measurements, selective U.S. export of supposed anti-corruption tools like polygraphs, budgetary non-response to increasing accountability pressures on such tools, and the broad, historical sense that corruption has always threatened collective well-being—but now that democratic publics are focused on security, they’re either missing or unable to make their governments grapple with the truly existential threats.

1. International corruption measurements

International corruption measurements, such as those produced by the World Bank, Transparency International, and Freedom House, produce a primary irony of the pathology of corrupt governance. Systematic, high-level corruption tends to be less visible in these measurements. One reason is that these measurements are vulnerable to systematic biases that make them good at measuring lower-level corruption like civil service bribery in LDCs (least developed countries) through citizen surveys—and bad at measuring higher-level, systematic corruption like federal electronic voting machine fraud. In crude terms, state and corporate lawyers in corrupt OECD nations with some of the best corruption rankings globally can simply legalize what elites want to do. This is what the American legal and political regime did in the case of the CIA’s kidnapping and torture program in the state realm, and big bank bailouts in the corporate realm. The regime is corrupt enough to formalize, legalize, and thus avoid (some) measurements of its corruption.

This is the case even in the context of war crimes, as illustrated by the 2002 American Service-Members’ Protection Act (aka the Hague Invasion Act). In the ASMPA, the U.S. explicitly reserved the right to invade an international criminal court if it ever attempts to hold and try U.S. military personnel or government officials (Human Rights Watch 2002). In other words, high-ranking American federal officials planning an illegal war along with a global program of kidnapping and torture passed a law pronouncing their unaccountability (Danner 2009, MacAskill and Borger 2004, U.S. Senate Select Committee on Intelligence 2014). That unaccountability is itself, ironically, a national security threat.

Recent empirical legal and psychological research suggests that when people perceive law enforcement as fair, they are more likely to share information and otherwise cooperate with police (Tyler & Huo 2002). Law enforcement and intelligence agencies that degrade rule of law in the name of advancing security, instead actively degrade the security they purport to promote. High-level corruption such as that reflected by the Hague Invasion Act involves official rule violations that are visible, high-level, systematic but unpredictable (as opposed to due process—often understood as systematic and relatively predictable application of the same laws to all citizens, regardless of race or creed), and widely perceived as unfair. Such corruption might well harm trust in government, and thus harm security in procedural justice terms, more than forms of corruption that are relatively predictable and low-level, like bribery. Indeed, bribery that is relatively standardized and reliable can be perceived as a rule of law improvement in areas where inconsistent bribery might otherwise hinder freedom of movement.[3]

So corruption perceptions indices are themselves ironically corrupt. They give more systematically corrupt elites a comparative measurement advantage. And indeed the organizations that compile global corruption (perceptions) indices are themselves bankrolled by those same globally dominant nation-states that gain the advantage (e.g., Falk 2012, Tucker 2008). So international corruption measurement as it is usually done looks like a soft power goodie that lets the global elite control the narrative about what nations can better lay claim to moral high ground. Countries whose elites are best at legalizing their rule of law violations—and controlling transnational organizations, be they telecommunications corporations collaborating in mass surveillance or neoliberal institutions of legal regime instantiation—win.

2. Selective anti-corruption tool exports

Selective anti-corruption tool exports produce another irony of the pathology of corrupt governance. For example, the U.S. forbids export of polygraph equipment to nations it considers particularly bad human rights violators, because the lie detector is prone to abuse as an instrument of psychological torture. Meanwhile, America exports to and requires adoption of polygraphs as part of anti-corruption programs in client states ranging from Mexico to the Bahamas, Bolivia, Guatemala, Honduras, and Iraq (U.S. Government Accountability Office, 2010; U.S. Department of State, 2010). In the U.S., polygraph programs have enabled discretionary abuses of power to take on a false veneer of neutral, scientific administration. For example, polygraphs have enabled recent whistleblower persecutions[4], anti-socialist and homophobic witch-hunts, and interrogations both overseas in the war on terror and at home in security screenings that government polygraphers and others complained were inappropriate (Alder 2007, Interviews 2009-11, Taylor 2012-4). At least one federal agency that refused to release data to enable testing for racial and gender bias in its polygraph program, the CIA, has repeatedly denied polygraph subjects the ability to complain about alleged equal opportunity violations in polygraphs—placing its polygraph division above the law, and lying to Congress about it (CIA 2005, Interview 2009, CIA 2010, in Taylor 2012). Polygraph programs deepen rather than ameliorating at least some forms of corruption.

Through that very mechanism—of weeding out people who step out of line, through means that looks scientific enough and security-relevant enough to discourage or prevent external accountability checks—polygraph programs help legitimize and stabilize corrupt regimes. By targeting people who question—authority, conformity, and wrong-doing, whatever or whomever its source—polygraph programs decrease the odds that a regime or institution will undergo meaningful reform from within. So selective lie detector exports to corrupt U.S. client states mask the export of interrogation protocols that screen for and silence witnesses to corruption, rather than reducing corruption itself.

3. Unaccountable accounting

Visible lack of financial accountability for resource expenditures that the government itself deems insufficiently evidence-based presents another irony of corrupt governance. As a pathology, high-level, systematic corruption should be hard to measure and easy to spread, as the ironies of global corruption measurements and selective anti-corruption tool exports suggest. But even programs associated with agencies with black budgets are visibly unresponsive to increasing fiscal accountability pressures.

For example, federal polygraph programs tended to expand significantly after the NAS reported they hurt security. Similarly, the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) and insiders have criticized the lack of accountability in funding and evidentiary standards for SPOT (Screening of Passengers by Observation Techniques), a next-generation behavioral lie detection program used in airport screenings that the ACLU alleges leads to racial profiling (U.S. Government Accountability Office, 2013; Winter and Currier, 2015). The program continues in the absence of sufficient scientific evidence supporting its use for enhancing security. Leading experts have expressed similar concerns about other next-generation lie detection programs, such as FAST (Future Attribute Screening Technology) and AVATAR (Interviews 2009-11). But such programs continue or grow despite the Department of Homeland Security touting, at best, the same hypothetical accuracy rate for FAST (80%) that National Academy scientists showed would make better-than-best-possible polygraph programs backfire and hurt the security they purport to advance (Christensen, 2008).

Budgetary non-response within law enforcement and intelligence agencies to increasing accountability pressures highlights the larger and less frequently discussed issue of potential criminal liability of individual corporate and governmental officials for security theater qua fraud. Individuals who profit from lying about lie detection in ways that are statistically likely to endanger security should but do not appear to face either profit losses or criminal charges. In theory, one could use the selective export of polygraphs in anti-corruption programs to jurisdiction-shop for a legal regime that might set a precedent of accountability.

Cases like that of Osama Mustafa Hassan (aka Abu Omar) show this approach to accountability can work, for some value of working. Omar is an Egyptian cleric whom Italy granted political asylum, before the CIA kidnapped and rendered him back to Egyptian security forces who then tortured him. Italian courts have sentenced Italian and American officials in absentia in Omar’s case, with at least one related extradition request (Sabrina de Sousa’s) pending (Staff 2016). Such accountability is inconceivable in the U.S. (Greenwald 2013). Yet, the Department of Justice filed a motion to dismiss de Sousa’s lawsuit against the U.S. government for diplomatic immunity (Santiago 2016). It serves U.S. interests for its courts to play hot potato with (when they can’t entirely ignore) politicized foreign trials of its citizens, because visibly interfering with other countries’ legal processes looks corrupt. Looking corrupt is for LDCs.

So jurisdiction-shopping can work as a mitigating solution for systematic unaccountability on the top. But its successes and failures thus far continue to highlight lack of due process: you can try to get to Sabrina in Portugal for what she did undercover in Milan—which she maintains was following directions. But you can’t touch George in Texas for what he did in the White House—like running Agent Sabrina’s chain of command, and constructing the legal infrastructure in which she apparently understood herself to be acting. Multiple foreign jurisdictions continue trying and failing to hold high-ranking U.S. military and civilian officials accountable for recent war crimes including torture (Emmons 2016). Jurisdiction-shopping for accountability at the top is likely to be an exercise in performance art for the foreseeable future.

4. Existential collective action problems

Finally, the pathology of corrupt governance generates the broad, historical irony of our existential collective action problems (CAPs). Surveillance (aka security) states currently preside over worst global failure to address existential CAPs in the known history of human societies. Corruption has always threatened collective well-being. With the advent of the endless global war on terror and the first waves of refugee crises that are likely to escalate along with climate change’s cascade effects, OECD publics now focus increasingly on security (e.g., terrorism, cybercrime, and demographic change) without understanding what are the truly existential security threats (e.g., climate change, arms trade, and mass surveillance). Corrupt governance and especially corrupt U.S. governance in the age of the neoliberal, military-industrial regime in a unipolar world pours finite resources into the oil and gas industry that keeps fossil fuel dependence the norm. Air pollution exposure already kills 7 million annually—around one in eight of total global deaths (World Health Organization 2014); avoidably unhealthy environments are linked to nearly one in four total global deaths (Vidal 2016). Arms trade keeps lethal means access high—inflating preventable violence (World Health Organization 2009). And the broader security industry propagates forms of dragnet telecommunications surveillance and other asymmetrical interactions that are prone to abuse against peaceful democratic organizers, scientists, artists, and publics at large (Chen 2015).

Meanwhile, CAPs that threaten civilization as we know it—the real security threats—are all but ignored. The over-arching CAP is the one philosophers from Plato to Marx analyzed in different historical contexts: growing structural inequalities decreasingly responsive to meritocratic processes, in tandem with political discourse that distracts democratic publics—like a pastry chef promising a sick child a more appealing cure than the one the actual doctor offers (Gorgias, in Dodds 1961), or an “opiate of the people” to dull pain rather than treating the underlying condition (Marx 1972). That problem keeps power structures captured by elites working for their small-group rather than the larger collective interest. This is one of the perennial problems of politics. It’s not going to go away, but we can address it better or worse.

More corrupt governance like we see in the U.S. post-Citizens United[5] means we’re addressing it worse. The political system is more corporate-captured, more buyable, in formally legal ways. This looks like a feedback effect, where an already corrupt legal regime formalized what was already political practice as legal precedent.

The other main global CAPs nestled within that over-arching CAP (of inequality generating captured political processes) that make us address it worse include mass surveillance at the tactical level and climate change at the strategic one. Mass surveillance—from lie detection programs to the illegal dragnet telecommunications surveillance Binney, Drake, Snowden, and others documented, and beyond—impairs activists, journalists, scientists, whistleblowers, and others from effectively communicating and acting in order to contest elite abuses of power. It enables various forms of COINTELPRO—counterintelligence programs that surveil, infiltrate, discredit, and disrupt domestic political organizations—and other retaliation, such as the federal coordination of corporate and state-level law enforcement efforts to surveil and suppress Occupy protests across the U.S. (Wolf 2012). So mass surveillance disrupts opposition of elite resource capture. This elite resource capture that perpetuates fossil fuel dependence is an existential threat to human society.

Climate change threatens the global ecosystem, kills hundreds of thousands annually, and may displace 200 million people by 2050 (Climate Vulnerable Forum 2012, Myers 2005, Nagelkerken & Connell 2015). But a paradigm shift away from the fossil fuel dependence driving the still-controllable parts of that threat would threaten elite interests. This looks bad for humanity.

That said, there are three areas where we might reasonably have some measured hopes for increased transparency and accountability, less corrupt governance, and more evidence-based policy. One is in successful criminal prosecution and prevention of high-level fraud as fraud. Another is in the potential of technology to mitigate against systematic biases, and another is in its related potential to speed up accurate decisions in some life-or-death situations.

1. Prosecuting fraud, banning pseudoscience

First, there are some recent cases of security theater being prosecuted as the life-endangering fraud it is. For example, the purveyor of a modern dousing rod that purportedly detected drugs and bombs on the same theory that divining rods purportedly detect water (the ADE 651) was recently sentenced to ten years in prison for fraud (Booth, 2013). That was a case of a Western government holding a Western individual criminally liable for committing security theater qua fraud. And indeed, we should talk about security theater as a crime, because of how fraudulent security practices endanger lives. But the fraud in this case affected an LDC. There is no apparent precedent for holding individual lie detectors operating within OECD nations in which they are commonly used (i.e., the U.S., Japan, and Israel) accountable for damages from fraud, despite common claims of 99% accuracy in judging truth or deception using polygraphs, voice stress analysis, and other tools that scientific consensus judges insufficiently evidence-based.

As discussed, this form of accountability does not appear to happen within OECD countries in the realm of security theater more broadly. This could change. Currently, a criminal ruling against a Google or Microsoft executive for selling the NSA mass surveillance that backfires, costing millions if not billions and endangering people, is unthinkable. Similarly, a criminal ruling against a federal polygraph division chief for knowingly running a fraudulent program that breaks the law while endangering national security is probably impossible in a country where federal law enforcement and intelligence agencies routinely, successfully argue that they can’t air their evidence in open court for security reasons.

As in the case of electronic voting machines (EVM), nontransparency in secretive, technology-mediated programs makes audit trails impossible, and thus makes larger-scale fraud easier for elites to perpetrate under a guise of neutral, scientific (or rather, sciencey) administration (Prasad, Halderman, Gonggrijp, Wolchok, Wustrow, Kankupati, Sakhamuri, and Yagati 2010). As in the case of EVM, a small group of dedicated opponents insisting that the same pattern applies in other contexts could change the rules. EVM opponents got them banned in Holland and Germany, and were barred from entering India because of related research efforts.

2. Testing technology as a cloak for—and weapon against—bias

Another hopeful development is the potential of technology to mitigate against systematic biases. Available evidence suggests that when you partly automate administrative decisions, like food stamp benefits calculation, medical diagnosis in some p

hases, and “credibility assessment” (the going euphemism for lie detection)—those decisions don’t then hide systematic biases that we want to keep out of them, like racial and confirmation (background) bias and their intersection (Wilde 2014). We know from recent U.S. field experiments that racial and confirmation bias appear to exist and to compound one another in blue-collar labor markets like restaurant hiring processes—making it harder for blacks, felons, and especially black felons to get work (Pager 2008).[6] But from a range of seven online survey experiments and two lab psychophysiology studies, my research suggests these biases do not systematically affect polygraph chart interpretation or similar technology-mediated decisions.

We need to continue testing technology to learn whether and in what field contexts it can institutionalize—or mitigate against—bias. Adequately statistically powered, independent field evidence was not available to determine whether my null racial bias results generalize to field conditions.[7] Federal polygraph researchers previously documented a disconnect between null experimental results like these, and observational evidence of racial bias in federal polygraphs (Reed 1996). Interviews with whistleblowers suggest federal agencies use polygraphs to get rid of people who are different or tell critical stories (e.g., CIA whistleblowers Ilana Greenstein and John Sullivan). Freedom of Information requests to and lawsuits against multiple federal agencies (e.g., CIA, FBI, NSA, and DOJ) resulted in documents illustrating similar sorts of abuses. Requests and lawsuits failed to produce federal polygraph program data releases that would have enabled testing for racial and other biases. This governmental nontransparency featured in a national investigative series—that also failed to get federal polygraph program data released (Taylor 2012-2014).

One might see formal Freedom of Information efforts in this context as a form of opposition resource capture, commonly taking years and thousands of dollars in legal service and filing fees. The growth of leak platforms such as WikiLeaks and Global Leaks suggests that some reformist forces within these particularly nontransparent state security apparatus, for example, agree. As reform from within becomes more obviously untenable, whistleblowing is increasingly the moderate, reformist option, next to infiltration and sabotage. Novel technological platforms increasingly support relatively safe, anonymous ways of employing that moderate option of contributing information vital to the public interest to independent publishers. These platforms represent one out-of-the box way in which technology can mitigate against bias (in this case, publication bias of official state and corporate narratives at odds with internal documents).

3. Testing technology’s effects on accuracy in life-or-death decisions

Finally, we can continue testing technology’s effects on accuracy in life-or-death decisions. Overly optimistic American use of Bayesian algorithmic machine learning in programs such as the NSA’s SKYNET may have cost thousands of innocent lives (Grothoff and Porup 2016). But other, more constrained uses of such algorithms might help promote speed and accuracy, saving lives. For example, the medical diagnosis decision support tool Isabel produces Bayesian-ranked differential diagnoses that may help patients and doctors alike identify high-impact/low-probability problems like necrotizing fasciitis from childhood chicken pox (in the case of the tool’s namesake—Isabel). Technologies like SKYNET, Isabel, and lie detectors can literally cost or save lives. We should know the difference.

Conclusion

The fantasy of lie detection is a powerful and potentially positive one—a dream that we can understand ourselves and others better and more scientifically, for the collective good. And technologies like medical diagnosis support tools really might help us get there, as long as we use them in evidence-based ways. Technology can force-multiply good or evil, like any tool. The deeper, darker American obsession is thus not lie detection per se, but surface perfection—we want more, better, faster, everything, from self-improvement to security. Just as the beauty industry poisons people in the name of perfecting bodies[8], so too does security theater endanger people in the name of perfecting security. Once we accept there is neither perfect body, nor perfect security, we can use technology—like fitness apps and surveillance cameras—and other, low-tech tools—like real-life social networks, jogging with a friend in the fitness realm or talking to your neighbors in the everyday security realm—to get a little closer. That might not help improve civilization’s odds in the big picture, but it can help individuals and communities have higher quality of life.

For all its scientific debunkers and their for-profit counterweights, lie detection is more than just a modern form of alchemy—or a revealing instantiation of man’s hunger to know what’s going on in other people’s heads and hearts better than perhaps we can even know ourselves. It’s also a useful case study at the intersection of mass surveillance and security theater, showing how collective action problems work in the era of Big Data. Systematic corruption, elite clientilism, and their confluence in the American military-industrial complex and its control of the globalized U.S. legal regime actively endanger the global ecosystem. Just as lie detection is a lie, the so-called security state threatens security. Holding to account the individual government officials and corporate heads responsible for spending billions on security programs like lie detection that backfire and endanger security does not appear to be possible from within. What does appear to be possible is contesting their spread in places where they are making new inroads, such as border crossings in Europe—and teaching people how to protect themselves from false positive results by demonstrating how easy lie detectors are to beat.

Bibliography

Alder, K. (2009). The lie detectors: The history of an American obsession. University of Nebraska Press.

Associated Press. (2015). Johnson & Johnson to pay $72m in case linking baby powder to ovarian cancer. The Guardian.

Balkin, J. M. (2008). The Constitution in the National Surveillance State. Minnesota Law Review, 93(1).

Booth, R. (2013). Fake bomb detector conman jailed for 10 years. The Guardian. http://www.guardian.co.uk/uk/2013/may/02/fake-bomb-detector-

BORDERS National Center for Border Security and Immigration. (2013). BORDERS’ AVATAR on Duty in Bucharest Airport. Website.

Campbell, D. T. (1998). The experimenting society. The experimenting society: Essays in honor of Donald T. Campbell, 11, 35.

Chen, Adrian. (2015). The Agency: From a nondescript office building in St. Petersburg, Russia, an army of well-paid “trolls” has tried to wreak havoc

all around the Internet — and in real-life American communities. The New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2015/06/07/magazine/the-

Climate Vulnerable Forum. (2012). The Climate Vulnerability Monitor, 2nd edition. DARA. http://www.thecvf.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/CVM2-

Committee to Review the Scientific Evidence on the Polygraph (National Research

Council (US)), National Research Council (US). Board on Behavioral, Sensory Sciences, National Research Council (US). Committee on National

Statistics, National Research Council (US). Division of Behavioral, & Social Sciences. (2003). The polygraph and lie detection. Haworth Press.

Christensen, B. (2008). Future Attribute Screening Technologies Precrime Detector. Technovelgy. http://www.technovelgy.com/ct/Science-Fiction-

Danner, M. (2009). The Red Cross torture report: what it means. The New York Review of Books, 56(7).

Dodds, E. R. (1961). Plato, Gorgias. A Revised Text with Introduction and Commentary.

Emmons, Alex. (2016). The Intercept. Former Guantánamo Commander Ignores Summons From French Court Probing Torture.

Falk, R. (2012). When an ‘NGO’ is not an NGO: Twists and turns under Egyptian skies. Al

Jazeera. http://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/opinion/2012/02/2012217132230738823.htm.

Feeney, M. (2015). Watching the Watchmen: Best Practices for Police Body Cameras. Policy Analysis No. 782. Cato Institute.

Greenwald, G. (2013). Italy’s ex-intelligence chief given 10-year sentence for role in CIA kidnapping. The Guardian.

http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2013/feb/13/italy-cia-rendition-abu-omar

—. (2014). No place to hide: Edward Snowden, the NSA, and the US surveillance state. Macmillan.

Grothoff, C, and J.M. Porup. (2016). The NSA’s SKYNET program may be killing thousands of innocent people: “Ridiculously optimistic” machine

learning algorithm is “completely bullshit,” says expert. Ars Technica

Hobbes, Thomas. Leviathan, 1651. Scolar Press, 1969.

Human Rights Watch. (2002). U.S.: ‘Hague Invasion Act’ Becomes Law.

https://www.hrw.org/news/2002/08/03/us-hague-invasion-act-becomes-law

Interviews, 2009-2011.

James, N, Analyst in Crime Policy, 7-0264. (2014). Congressional Research Service.

Report IN10142. http://www.fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/IN10142.pdf

Kuklinski, J. H., & Quirk, P. J. (2000). Reconsidering the rational public: Cognition,

heuristics, and mass opinion. Elements of reason: Cognition, choice, and the

bounds of rationality, 153-82.

Leo, R. A. (2008). Police interrogation and American justice. Harvard University Press.

Locke, J. (2014). Second Treatise of Government: An Essay Concerning the True

Original, Extent and End of Civil Government. John Wiley & Sons.

Lynch, M., Cole, S. A., McNally, R., & Jordan, K. (2010). Truth machine: The

contentious history of DNA fingerprinting. University of Chicago Press.

MacAskill, E., and J. Borger. (2004). Iraq war was illegal and breached UN charter, says

Annan. The Guardian. http://www.theguardian.com/world/2004/sep/16/iraq.iraq

Marx, K. (1972). The Marx-Engels Reader (Vol. 4). New York: Norton.

Mearian, L. (2015). As police move to adopt body cams, storage costs set to skyrocket:

Petabytes of police video are flooding into cloud services. Computerworld.

Mole, B. (2013). NSF cancels political-science grant cycle: US funding agency said to be

dodging restrictions set by Congress. Website: http://www.nature.com/news/nsf-cancels-political-science-grant-cycle-1.13501.

Myers, N. (2005). Environmental refugees: an emergent security issue.

Nagelkerken, I., & Connell, S. D. (2015). Global alteration of ocean ecosystem

functioning due to increasing human CO2 emissions.Proceedings of the National

Academy of Sciences, 112(43), 13272-13277.

National Aeronautics and Space Administration, Goddard Institute for Space Studies.

(2016). Surface Temperature Analysis, Land-Ocean Temperature Index. Via Bob

National Research Council. (2009). Strengthening forensic science in the United States:

A path forward.

Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe, Office for Democratic Institutions

and Human Rights. (2007). The Netherlands Parliamentary Elections:

OSCE/ODIHR Election Asses

sment Mission Report.

Pager, D. (2008). Marked: Race, crime, and finding work in an era of mass

incarceration. University of Chicago Press.

Pielke, R.A. Jr. (2007). The Honest Broker: Making Sense of Science in Policy and

Politics. Cambridge University Press.

Prasad, H.K., Halderman, J.A., Gonggrijp, R., Wolchok, Wustrow, Kankipati, Sakhamuri,

Yagati. (2010). Security Analysis of India’s Electronic Voting Machines.

Proc. 17th ACM Conference on Computer and Communications Security

https://indiaevm.org/evm_tr2010-jul29.pdf

Priest, D., and W. Arkin. (2010). Top Secret America. The Washington

Post. http://projects.washingtonpost.com/top-secret-america/

Reed, S.D. (1996). Subculture Report: Effect of Examiner’s and Examinee’s Race on

Psychophysiological Detection of Deception Outcome Accuracy. Polygraph

25(3): 225-242.

Santiago, M. (2016). Portugal court orders CIA agent extradited to Italy in rendition case.

Schneier, B. (2006). Beyond fear: Thinking sensibly about security in an uncertain world.

Springer Science & Business Media.

Simon, H. A. (1972). Theories of bounded rationality. Decision and organization, 1(1),

161-176.

SIPRI Military Expenditure Database 2015.

Staff. (2016). Portuguese court backs ex-CIA agent’s extradition to Italy. The Local. http://www.thelocal.it/20160115/portuguese-court-backs-ex-cia-agents-extradition-to-italy

Taylor, M. (2012-2014). The Polygraph Files. McClatchy Newspapers. Reporting on

documents, sources, and research author released to McClatchy following years of

interviews, FOIA requests and lawsuits (most represented by K. McClanahan),

and experiments.

Tilly, C., Evans, P. B., Rueschemeyer, D., & Skocpol, T. (1985). War making and state

making as organized crime (pp. 169-191). Cambridge: Cambridge University

Press.

Tucker, C. (2008). Seeing through Transparency International. The

Guardian. http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2008/may/22/seeingthroughtransparencyin

Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1981). The framing of decisions and the psychology of

choice. Science, 211(4481), 453-458.

Tyler, T. R., & Huo, Y. (2002). Trust in the Law: Encouraging Public Cooperation with

the Police and Courts Through: Encouraging Public Cooperation with the Police

and Courts Through. Russell Sage Foundation.

U.S. Department of Justice, Office of the Inspector General, Evaluation and Inspections

Division. 2006. Use of Polygraph Examinations in the Department of Justice. I-

2006-2008.

U.S. Department of State. (2010). Program and Budget Guide. Bureau for International

Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs.

U.S. Government Accountability Office. (2013). Aviation Security: TSA Should Limit

Future Funding for Behavior Detection Activities. GAO-14-158T.

http://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-14-158T

U.S. Government Accountability Office. (2010). Mérida Initiative: The United States Has

Provided Counternarcotics and Anticrime Support but Needs Better Performance

Measures. Report to Congressional Requesters GAO-10-837.

U.S. Senate Select Committee on Intelligence. (2014). Committee Study of the Central

Intelligence Agency’s Detention and Interrogation Program, Foreword by Senate

Select Committee on Intelligence Chairman Dianne Feinstein, Findings and

Conclusions, Executive Summary. Declassification Revisions December 3, 2014.

Vidal, J. (2016). Environmental risks killing 12.6 million people, WHO study says. The

Wilde, V. (2014). Neutral Competence? Polygraphy and Technology-Mediated

Administrative Decisions. Ph.D. Dissertation.

http://files.gendo.nl/Books/VKW_Dissertation_-_Full_02-02-14.pdf

Winter, J., and C. Currier. (2015). Exclusive: TSA’s Secret Behavior Checklist ot Spot

Terrorists. The Intercept. https://theintercept.com/2015/03/27/revealed-tsas-closely-held-behavior-checklist-spot-terrorists/

Wolf, N. (2012). Revealed: how the FBI coordinated the crackdown on Occupy. The

Guardian. http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2012/dec/29/fbi-coordinated-crackdown-occupy

World Health Organization. (2009). Guns, knives, and pesticides: reducing access to

lethal means. Series of briefings on violence prevention: the evidence.

http://www.who.int/mental_health/prevention/suicide/vip_pesticides.pdf

World Health Organization, Public Health, Social and Environmental Determinants of

Health Department. (2014). 2012 air pollution reports.

http://www.who.int/phe/health_topics/outdoorair/databases/FINAL_HAP_AAP_BoD_24March2014.pdf?ua=1

Acknowledgments

The author thanks blameless research funding sources—a National Science Foundation Postdoctoral Fellowship, NSF Doctoral Dissertation Research Improvement Grant, University of Virginia Raven Society Fellowship, UVA Society of Fellows Fellowship, Louise and Alfred Fernbach Award for Research in International Relations, and William McMeekin, Michael & Andrea Leven, and Bernard Marcus Institute for Humane Studies Fellowships—and guiltless shepherds including Michele Claibourn, Stephen Fienberg, Clay Ford, George Klosko, Sidney Milkis, Jos Weyers, and Nick Winter.

[1] Other such case studies include traditional forensic science tools with similarly insufficient evidence bases, such as bite mark analysis and even in some senses the gold standard of DNA fingerprinting, and newer incarnations of old policing tools, such as the rebirth of dragnet or bulk communications surveillance in the form of privatized tech companies’ collaboration with secret government programs later ruled illegal (Greenwald, 2014; Lynch, Cole, McNally, & Jordan 2010; National Research Council 2009).

[2]

One can also envision a possible future in which the outcome of a false positive AVATAR or other next-generation, border checkpoint “lie detector” result is worse for the individual, who might subsequently be denied entry to a country where he is seeking asylum or refugee status, and thus returned to a country where he’s likely to die.

[3] For example, imagine you’re a vegetable truck driver who crosses an Eastern European border every week. The border guard stops you and says you’ll have to fill out a form to cross. It will take three days to process the paperwork, at which point your produce will be rotten. You the driver can’t afford to bribe him. You’re merely an agent of the principal, the business owner. So the owner has to give you enough money for the bribe. But the border guard will take whatever money the driver appears to have—and the driver will keep whatever’s leftover. It helps the owner to know what amount the bribe needs to be consistently. That creates a form of rule of law that promotes freedom of movement and trade, in comparison with systems of bribery that are relatively venal and unpredictable. This is one reason President Putin has some popularity in Eastern Europe. Some reports suggest that his strong centralized power has standardized corruption in ways that functionally create some rule of law. The stock rebuttal is that Hitler made the trains run on time: efficiency in implementing procedural rule of law and justice can be entirely different things.

[4] For example, CIA whistleblowers Ilana Greenstein and John Sullivan report being polygraphed out of the Agency after raising concerns. Sullivan was a 31-year veteran CIA polygrapher who had gotten the required Publication Review Board for his memoir documenting polygraph division fraud and abuse. Source: Interviews, 2009-2011.

[5] Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission, No. 08-205, 558 U.S. 310 (2010)—the campaign finance ruling that made corporations people and money part of their Constitutionally protected free speech according to the U.S. Supreme Court.

[6] Pager’s results did not attain statistical significance. Due to expense, the field experiment was probably inadequately statistically powered. Her hypotheses and the findings that supported them were not controversial enough that Princeton University Press cared.

[7] Furthermore, some results suggested bias can seep into technology-mediated decisions in invisible, scientific-seeming ways. In one study, racial stereotypes seem to affect how people interact with a Bayesian-updating medical decision support tool in a way that has ordering effects. Such an ordering effect might change the differential diagnosis a physician produces while trying to diagnose a patient. But in my study, ordinary people using the tool did not lose diagnostic accuracy due to the ordering effect. See working paper at /overriding-race-and-class-bias-in-technology-mediated-diagnosis/.

[8] E.g., in a recent ruling, a Missouri jury ordered pharmaceutical company Johnson & Johnson to pay $72 million to the family of a woman who died of ovarian cancer after using Johnson & Johnson talcum powder regularly. The family’s attorney argued the company knew of the link between its product and cancer, and pursued its bottom line instead of acting on the evidence (Associated Press 2015).