Today I visited the Victoria & Albert Museum in London, “the world’s greatest museum of art and design.”

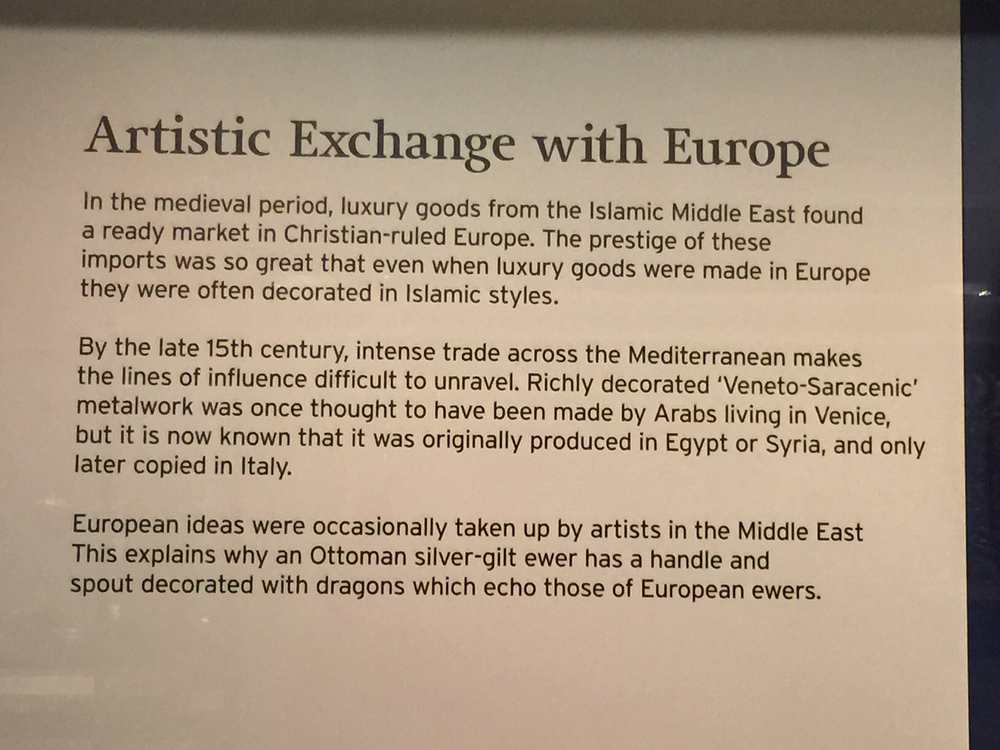

The V&A is full of what were formerly luxury goods. It hit me as soon as I walked in that it might be hard to tell what distinguishes luxury goods made in response to market demand now, and luxury goods made in response to market demand in other times and places that you can only look at in a museum now. So I meant to go to Tiffany’s after to ask myself that question, but spent too long at the V&A to make it.

Luckily, insofar as that’s an answerable question, the stuff at the V&A answers it.

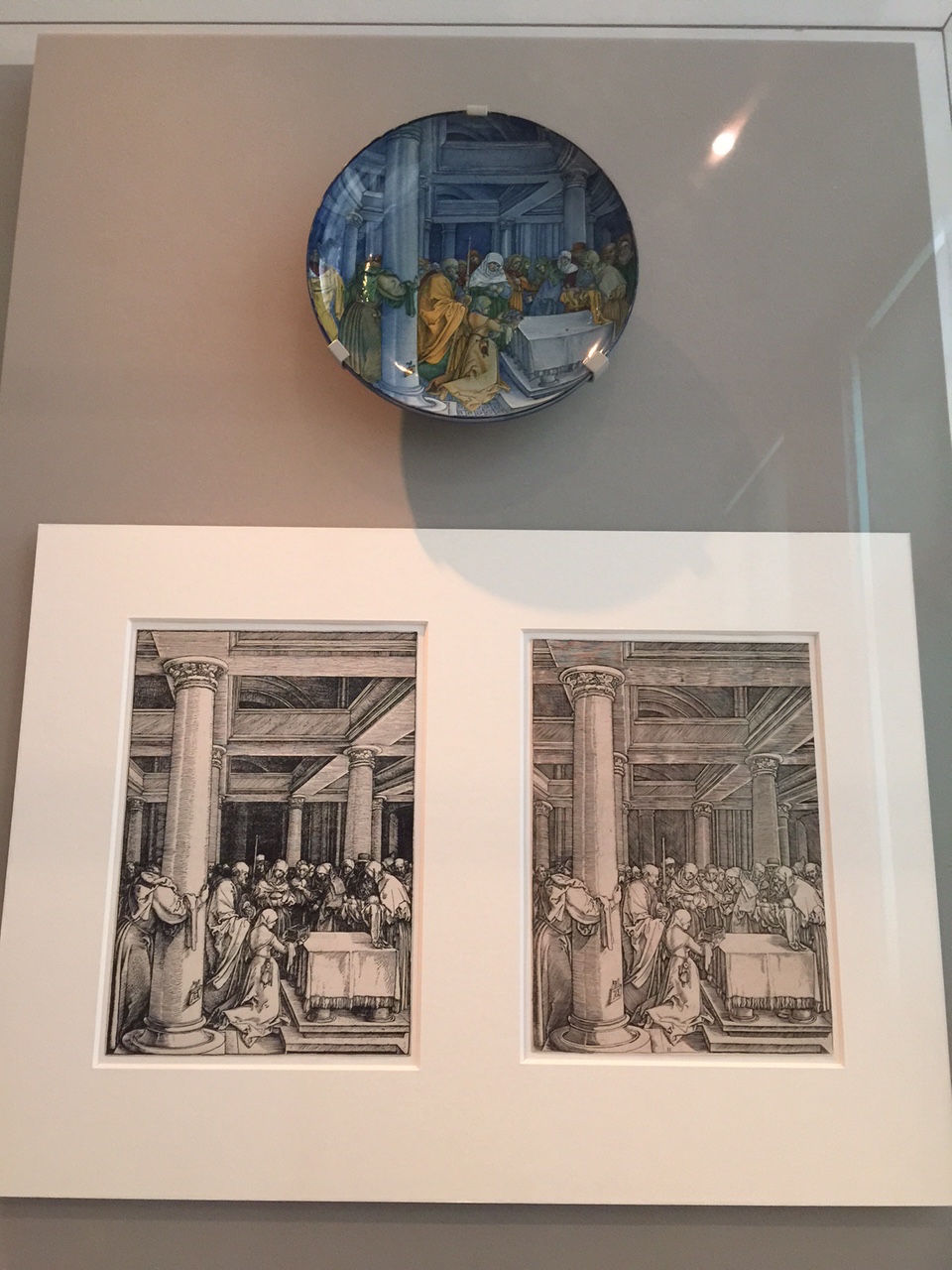

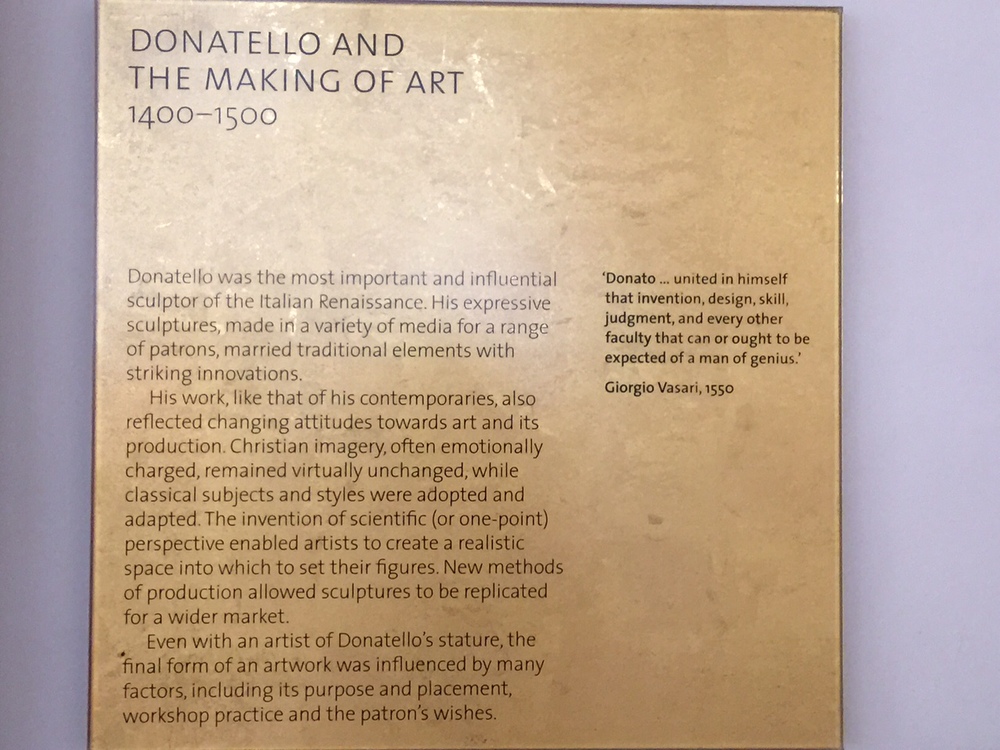

The difference between luxury goods and fine art is market demand. We associate luxury goods with the market economy and art with the gift economy—a totally different spirit. But actually, good movies can be fine art and have mass appeal. And great artists in ages past made luxury goods that were also fine art for their patrons. For instance, Donatello made the Medici this lovely fountain.

The tortoise at the base was a Medici symbol. Brings new meaning to the expression “it’s turtles all the way down.” Fine artists like Donatello cultivated relationships with rich patrons, fellow artists, and apprentice workers (who often did the bulk of what we might consider the work in famous artist’s workshops past)—just as successful artists and other entrepreneurs today cultivate relationships with business partners, venture capitalists, and other colleagues and supporters. The market aspect and the gift or calling aspect of the work were not opposed, although Donatello’s not around to ask about if he felt they were in tension.

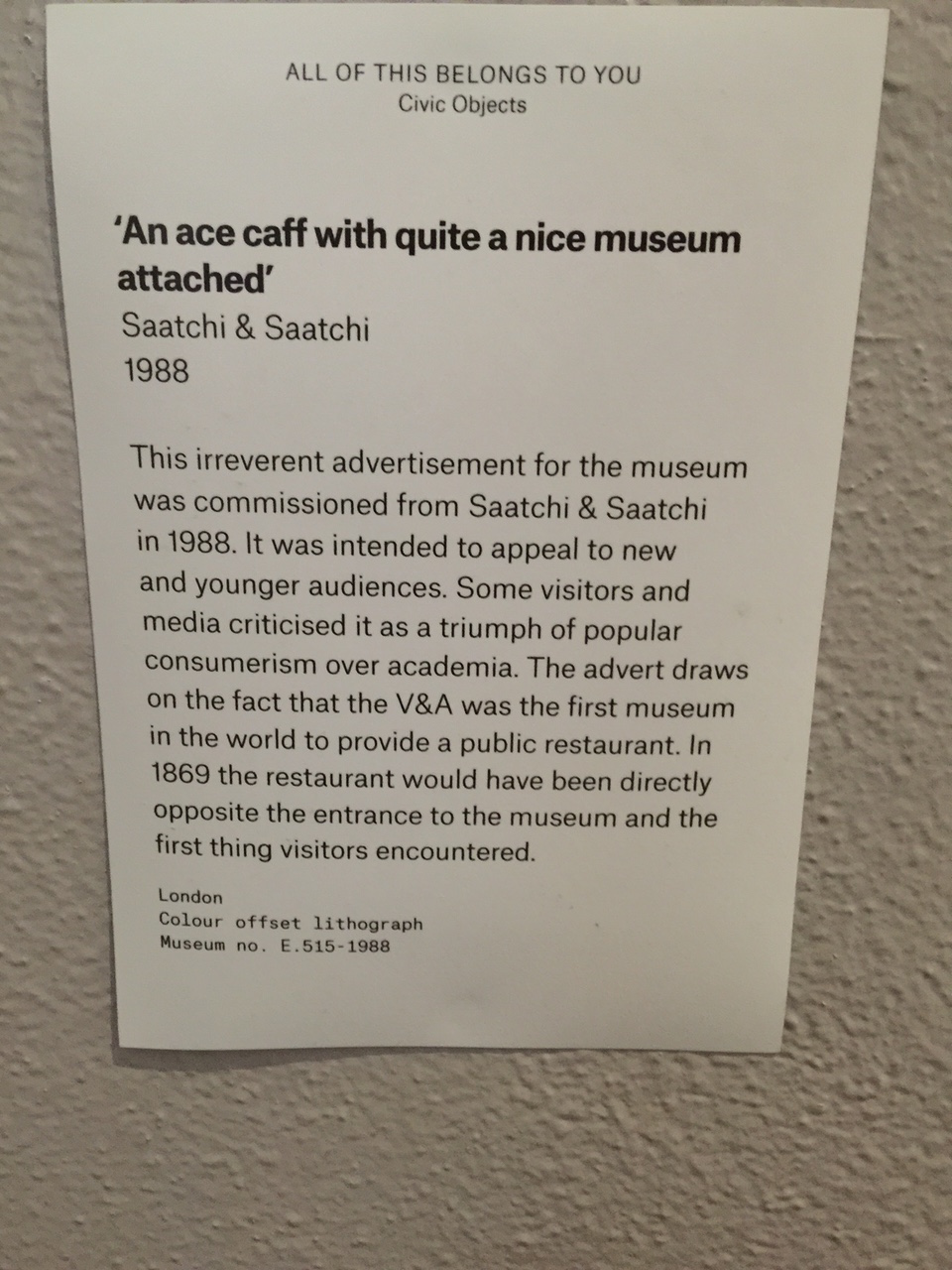

How does that easy fellowship of good money and good art mesh with the spirit of the quote in the V&A restaurant-café? Saatchi caused a stir commercializing the museum’s draw in this ad in the 80s:

But the café itself bears a consistent inscription—“There is nothing better for a man than like his soul enjoying good in his labor.”

As if to say—do your work, what you enjoy and lose time doing, and thrive in that. There’s not necessarily a conflict between following your heart and thriving in market terms. Yet this is not a message artists are used to hearing. We’re used to hearing something more like the inscription over the garden at the V&A—go for the wisdom, not for the gold.

Maybe because we’re rightly squeamish about monetizing everything. Things of the heart—like sex, childbearing, and art—sit in uneasy relation to the market in some ways. Prostitution is still illegal in lots of places, the baby market is a weird gray market in lots of ways, and the V&A, like a lot of fine art museums, is publicly owned.

According to staff, it’s 60% government funded, with the rest of its revenues coming from merchandizing and other things (presumably private funders). This frees it to experiment with art projects like V&A Music Resident Liam Byrne’s’s one-on-one baroque viola performance, in which the visitor climbs in a wooden chimney and feels the good vibrations of performance as public good.

Liam’s residency is a revelation, reclaiming the intensely tangible and intimate nature of music from the digital world. His project is one that could only happy through a supporting organization like the V&A, that’s looking to contextualize period music and make its own art exhibits more interactive—without profit.

Yet, art like this also has the perverse effect of making creative work seem less rather than more accessible in some respects. By placing art in a museum, at a remove from everyday life and outside the realm of normal business, it lends credence to the idea that there is a necessary tension between market and gift economy art, or luxury goods and fine art at the upper end of the market.

But just as you can sell the idea of sexiness without selling sex—automobile marketers do little else—so too can you sell the idea of art without selling its soul.

Or at least, that is what I am going to learn how to do this year, whether or not it happens to be possible.

Like anything else, art can be sold as luxury good or common merchandise, experience or public good, idea or thing. Our ideas about its worth and place in the world are what constrain its possibilities. So the art of the possible in art, like the art of the possible in politics, is a matter of the story we choose to tell.