Today I met with Aidan Fitzpatrick, Founder & CEO of Reincubate and Keep Calm Network. He was kind enough to give me a whole hour. And I got the best possible outcome of any business meeting—more and better questions, a reading list, and that warm, fuzzy feeling that I’m not alone in the search for intelligent life (and genuine value generation) in the universe.

More and Better Questions

Aidan started out asking me what the ideal outcome of the meeting was. I can’t remember what I said, but I remember how it made me feel: like I was in charge of the interaction and what I wanted mattered. There I was, unemployed, indebted from attempting to launch my own business, crashing with a friend of a friend in a foreign country because my spidey sense says I need to travel and make art right now—and suddenly I was running a meeting with the CEO of a company I admire because it does good in the world using art and ideas.

Maya Angelou said people will forget what you said and did, but not how you made them feel. It’s true. So the question I didn’t ask then that I have to ask myself now, as a businessperson and a human being, is how I can be more like Aidan in this way. When I blog, how can I do a better job making readers feel important, putting them in charge? When I paint, write, sing? On one hand, art is about pouring your heart out. But on the other hand, it’s about offering that outpouring to other people, to keep them company in the world and make them feel like I did in this meeting. Like they’re not just experiencing Harry Potter’s adventures, but in a sense writing them, too.

This weekend, I was a bit stuck on the plan-test-do art business conundrum. Like a lot of venture capitalists and artists, Aidan comes down firmly on the test side for business, and the do side for art. But on both fronts, his answers raised more and better questions.

Like most people I’ve talked with who have a history of making successful products and running successful businesses, Aidan’s businesses tend to happen organically. This makes me feel better about still struggling to write a full business plan.

But making businesses happen organically still takes a lot of work and specifically a lot of dialogue with the market. It takes validation experiments, whether you run them consciously using tools like Google Pay Per Click ads and Launch Rock, or unconsciously like the Beatles playing Hamburg strip clubs until they got their sound, or the feel of their process for making it.

This sort-of radio tuning principle is central to the way markets work as efficient information environments. Visually and conceptually it also shares a lot with Hedy Lamarr’s spread-spectrum singing and missile defense, Pandora Internet radio, and the central insight about mutual recognition that I’m trying to channel in allegorical poem-painting form in the next Where the Wilde Thinks Are (series) book I’m writing, that’s like The Lorax for policing.

I have a lot of work to do communicating what I’m talking about here better, but it’s basically about how deep listening lets us make something much better in collaboration than we could make by ourselves. It’s about the sociality of dreams. And it’s about constraint.

One of the terms of art Aidan introduced me to is that of “constrained media.” Andrew Chen has written about how the constraints of media like Twitter or Keep Calm create communication norms implicitly. That makes me think this sort of implicit constraint is the trick to generating communication norms—positive, respectful, honest, no Mohammed toons—to counter the meme-ification of extremist recruiting online—without being explicit about such constraint when free speech is part of the issue.

It also makes me wonder: What great, unanswered questions of emotional intelligence we can put to this computing resource that is social media, to take the bounds of social knowledge farther like we were able to calculate pi farther using computers? If we can harness its intelligence through the right constraints, what can we learn?

More and better questions:

– If online media generates positive communication norms through constraint but social media is too big to effectively moderate, what constraints keep it so you’re effectively inviting people to play a game or conduct a thought experiment with you? How do you make your constrained, interactive content game, not curation?

– What’s my next step in launching my art business, in terms of harnessing the social intelligence of the live web and constrained media? For simplification sake, let’s say I have three options, one on each pole and one in the middle of the validate-versus-create spectrum.

o At the create end of the spectrum, I could put out a book in some form—e.g., Kindle—and try to validate the market for it.

o At the validate end of the spectrum, I could test a series of book covers/ideas using Launch Rock and Pay Per Click ads before writing a thing. I think Aidan mentioned both James Altucher and Tim Ferriss do this.

o In the middle of the spectrum, I could use Google Pay Per Click to look at click through rates to get the best title for an existing draft, and collect email addresses for bigger launch—treating Amazon Kindle publication not as a test and short-term goal, but rather as a game and longer-term goal. A game where you want to be on the front page first, get a certain number of hits in a certain amount of time to maximize your chances of getting more momentum for more sales.

– Why can’t I get away from this validate-create duality? It’s dumb. Conceptually, the duality collapses. Creation and validation are one and the same because we’re social creatures—even poets and painters. But in practice, this is a real tension for art as a business.

– Is it bad strategy to keep learning by doing this way? I read a ton and then talk to people and discover I wasn’t even asking the right questions. I make and toss entire websites, prototypes, cities. (Just kidding—miss you, Boston.) Or is this how all successful entrepreneurs do it—starting with the meta idea and working through the mistakes to, hopefully, profit—but certainly, value generation?

The Reading List

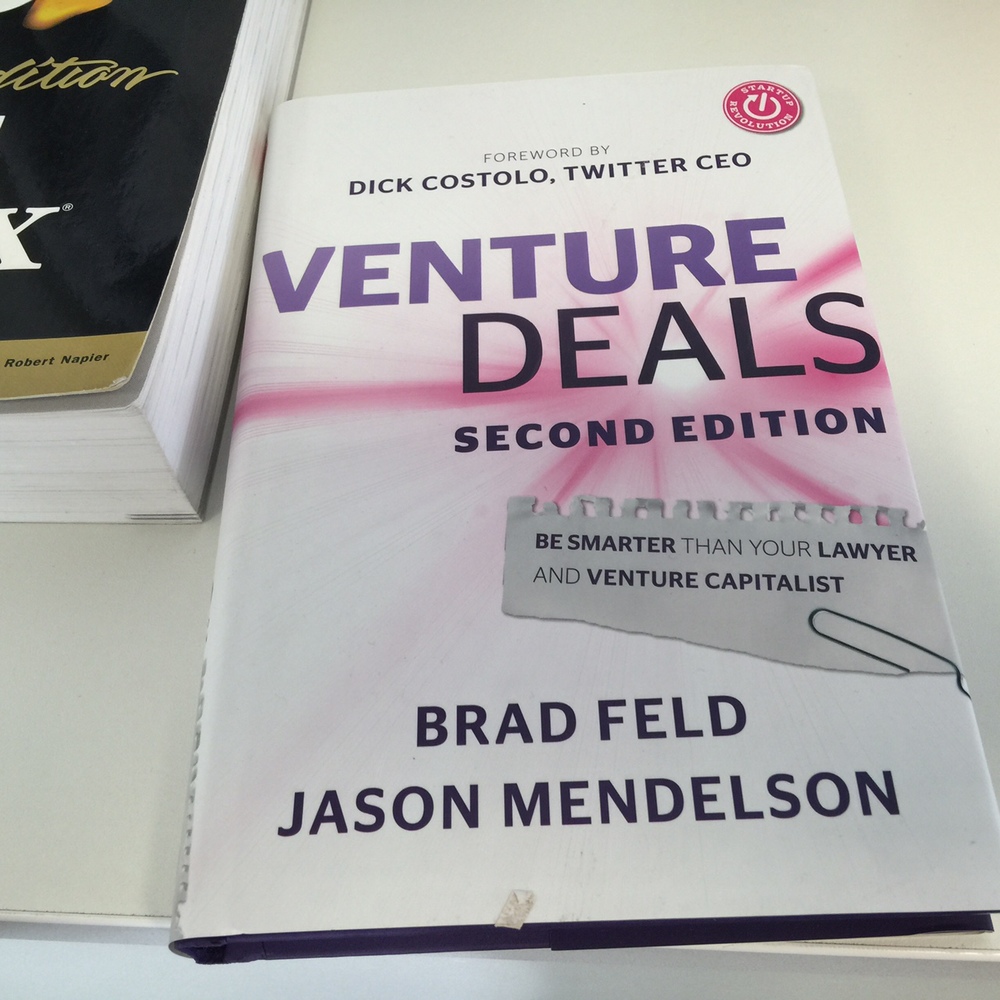

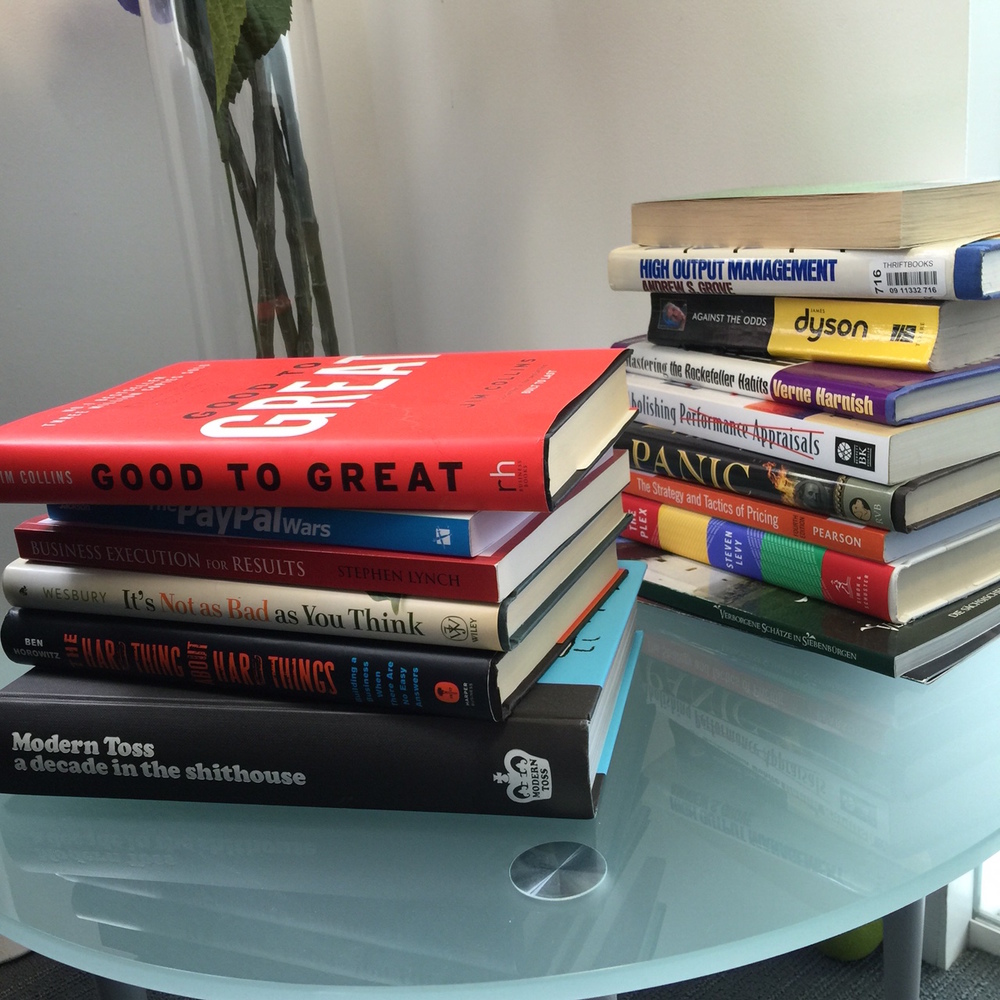

Ever think to yourself, “Geez this website and business are beautiful, I wonder what the CEO has been reading?”

Me, too.

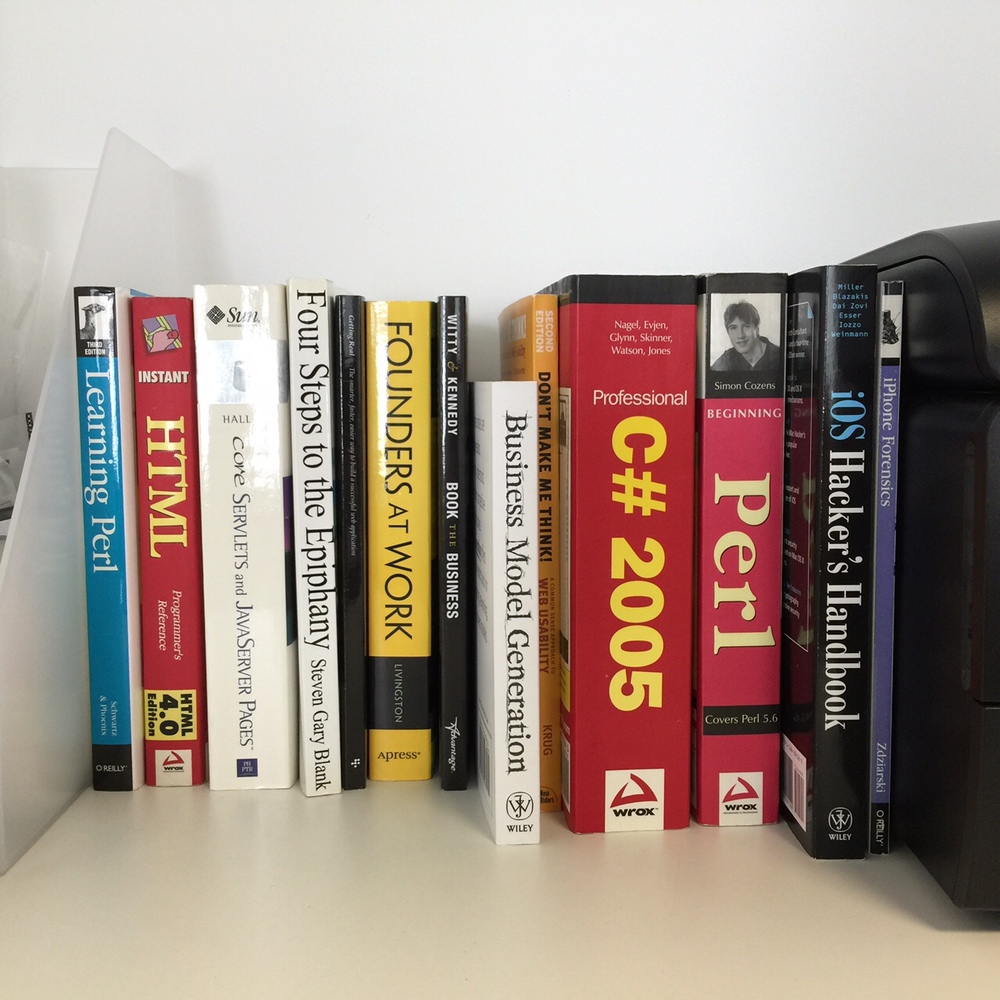

So I snooped around his office photographing all the books.

At the end, my list was too long, so he gave me a shortlist:

1. The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People, by Stephen Covey,

2. Good to Great, by Jim Collins, and

3. Mastering the Rockefeller Habits: What You Must Do to Increase the Value of Your Fast-Growth Firm, by Verne Harnish.

One of the products I want to create after I figure out how to launch my art-for-world-peace business is a cure for sleep. So I can work and read all night instead, but still make sense in the morning.

The Intelligent, Caring, and Hilarious Universe

All my business meetings lately seem to end with discussion of the universe. The intelligent, caring, and hilarious universe has been a main character in the story of my life this year. She has lots of eyes, wings, and waves. She’s a metaphor for social networks in some senses—and the way the “alive web” brings machine computing power to emotional and social intelligence.

Aidan asked if I had any other questions, and I used the opportunity to ask for his opinion on the drop-shipping model Tim Ferriss and others propound. Most people love or hate Tim Ferriss, he responded. And in the way being around someone intelligent and caring can up your own analytical and emotional intelligence, his own response—about attention to value—made me put my finger on why I haven’t been able to bring myself to even try the drop-shipping game.

There’s something resembling an easy step-by-step money-making process there. You find a product online that relates to an area of your expertise. You might validate the market for it using Pay Per Click ads on Google. And then you make and advertise a website that resells it. Buy in bulk, sell through middle-men online. You never have to deal with the product. You’re effectively just driving the traffic and taking a cut, as I understand it. Do the same thing with services, like web design, research assistance, or social media management—or other people’s time as you advise them in your book or on your website to play this game—and the same model is called arbitrage. So in the increasingly service-oriented economy, most businesses profit from human forms of drop-shipping.

One of the reasons art businesses are so hard to conceive and profit from is that it’s not really a good or a service you’re trying to sell. It’s an idea. Ideas may help sell other good and services—like the idea of happiness helps sell cars and candybars—but they’re in a different category altogether. And they’re what art sells, what it is. It should be the most profitable type of business in the world, because ideas are free.

Anyway, drop-shipping and some forms of arbitrage are morally problematic insofar as they don’t generate obvious value. Maybe you can help people save money by buying a good in bulk at a huge discount and reselling it online at only a partial discount, so you and the customer base both gain in a sense. But it doesn’t feel right.

The reason I left a Harvard postdoc to launch my own art business even though that is, in many senses, a totally crazy move, is because I have faith. I have faith in the goodness in myself, others and the world—in my ability to recognize and develop that goodness—and in the intelligent, caring, and hilarious universe to recognize that development and reward me. Trying to make money any old way doesn’t keep that faith. That’s not what embracing money as a metaphor for value and trusting that the market has some sense is about.

It’s about making art that makes people’s lives better. But I’m still trying to figure out what that means.